English - comment

TRANSFORMATION OF GEOMETRICAL FIGURES

This chapter deals with the method of combination or difference of two separate squares into a square and the transformation of a square into a rectangle, an isosceles trapezium or a circle and vice versa.

CONSTRUCTION of a SQUARE BEING SUM OF, DIFFERENCE BETWEEN, TWO SQUARES

विश्वास-प्रस्तुतिः

नानाचतुरश्रे समस्यन्कनीयसः करण्या वर्षीयसो वृध्रमुल्लिखेत् । वृध्रस्याक्ष्णयारज्जुः समस्तयोः पार्श्वमानी भवति १

English

If it is desired to combine two squares of different measures, a (rectangular) part is cut off from the larger (square) with the side of the smaller; the diagonal of the cut-off (rectangular) part is the side of the combined square. (Alternatively: If it is desired to combine two squares of different measures, a rectangle is formed with the side of the smaller (square) (as breadth) and that of the larger (as length); the diagonal of the rectangle (thus formed) is the side of the combined square).

English - comment

2.1-2.2. These two rules of Baudhāyana give the methods of construction of a square as the sum and difference of two different squares.

Here three technical terms, hrasiyasaḥ, varṣīyasaḥ and vṛddhram are used. According to Kapardisvāmi,1 hrasīyasa means the side of the smaller square, varṣīyasa the side of the larger square and vr̥ddhram the rectangular portion (dirghacaturafram).

Method of combination (samāsa).

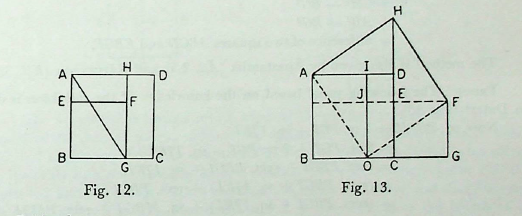

For the combination of a smaller square EBGF with another square ABCD, this rule of Baudhāyana suggests that the rectangular portion ABGH is cut off by the side of the smaller square whose side is equal to BG. Then AG of this cut-off portion will be the side of the combined square (Fig. 12).

Evidently,

\(AG^2 = AB^2 + BG^2 = sum of two squares.\)

The same method is also given by Āpastamba (Āśl. 2.4) and Kātyāyana (Kśl. 2.13).

PROOF: Datta2 has suggested the following proof of this proposition (Fig. 13).

sq. ABCD + sq. ECGF

\(= tr. ABO + tr. AOI + tr. OFG + tr. OFJ + sq. IJED\)

\(= tr. ADH + tr. AOI + tr. HEF + tr. OFJ + sq. IJED\)

= sq. AOFH

or, \(AB^2 + CG^2 = AO^2\)

Method of difference (nirhāra).

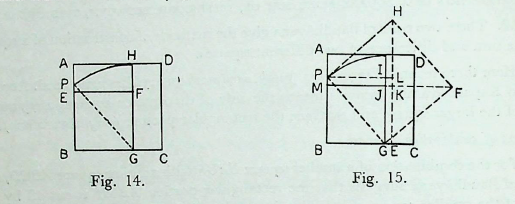

To construct a square equal to the difference between a smaller square EBGF and other square ABCD, the rule Bśl. 2.2 suggests that the rectangular portion ABGH is cut off by the side BG of the smaller square. Then the side GH of the cut off portion is allowed to fall on AB, and P is the point where it falls. Here GH = GP. Then BP is the side of a square which is equal to the difference of the squares ABCD and EBGF (Fig. 14).

Evidently,

\(= BP^2 = GP^2 - BG^2\)

\(= GH^2 - BG^2\)

\(=AB^2 - BG^2\)

= difference of two squares ABCD and EBGF.

The method is also given by Āpastamba (Asl. 2.5) and Katyāyana (Kŝl. 3.1). PROOF: The following proof based on the knowledge of the sulbakāras is due to Datta3 (Fig. 15).

Now, sq. \(PGFH = 4 tr. PGI + sq. IJKL\)

\(= 2 tr. PGI + 2 tr. PGI + sq. IJKL\)

\(= rect. PBGI + rect. PBGI + sq. IJKL\)

= (rect. PBGI + sq. IJKL) + rect. PBGI

= (rect. PBGI + sq. IJKL) + sq. MBGJ + rect. PMJI

= (rect. PBGI + sq. IJKL + rect. PMJI) + sq. MBGJ

= (rect. PBGI + sq. IJKL + rect. JGEK) + sq. MBGJ

= sq. PBEL+ sq. MBGJ

or, sq PBEL = sq. PGFH - sq. MBGJ

.. \(BP^2 = PG^2 - BG^2\)

or \(BP^2 = AB^2 - BG^2\)

मूलम्

नानाचतुरश्रे समस्यन्कनीयसः करण्या वर्षीयसो वृध्रमुल्लिखेत् । वृध्रस्याक्ष्णयारज्जुः समस्तयोः पार्श्वमानी भवति १

विश्वास-प्रस्तुतिः

चतुरश्राच्चतुरश्रं निर्जिहीर्षन्यावन्निर्जिहीर्षेत्तस्य करण्या वर्षीयसो वृध्रमुल्लिखेत् । वृध्रस्य पार्श्वमानीमक्ष्णयेतरत्पार्श्वमुपसंहरेत् । सा यत्र निपतेत्तदपच्छिन्द्यात् । छिन्नया निरस्तम् २

English

If it is desired to remove a square from another, a (rectangular) part is cut off from the larger (square) with the side of the smaller one to be removed; the (longer) side of the cut-off (rectangular) part is placed across so as to touch the opposite side; by this contact (the side) is cut off. With the cut-off (part) the difference (of the two squares) is obtained.

मूलम्

चतुरश्राच्चतुरश्रं निर्जिहीर्षन्यावन्निर्जिहीर्षेत्तस्य करण्या वर्षीयसो वृध्रमुल्लिखेत् । वृध्रस्य पार्श्वमानीमक्ष्णयेतरत्पार्श्वमुपसंहरेत् । सा यत्र निपतेत्तदपच्छिन्द्यात् । छिन्नया निरस्तम् २

विश्वास-प्रस्तुतिः

समचतुरश्रं दीर्घचतुरश्रं चिकीर्षंस्तदक्ष्णयापच्छिद्य भागं द्वेधा विभज्य पार्श्वयोरुपदध्याद्यथायोगम् ३

English

A square intended to be transformed into a rectangle is cut off by its diagonal. One portion is divided into two (equal) parts which are placed on the two sides (of the other portion) so as to fit (them exactly).

मूलम्

समचतुरश्रं दीर्घचतुरश्रं चिकीर्षंस्तदक्ष्णयापच्छिद्य भागं द्वेधा विभज्य पार्श्वयोरुपदध्याद्यथायोगम् ३

विश्वास-प्रस्तुतिः

अपि वै तस्मिंश्चतुरश्रं समस्य तस्य करण्यापच्छिद्य यदतिशिष्यते तदितरत्रोपदध्यात् ४

English

Or else, if a square is to be transformed (into a rectangle), (a segment) of it is to be cut off by the side (of the rectangle); what is left out (of the square) is added to the other side. (Like Āśl. 3.1, the rule is defective and does not lead to proper geometrical operation).

English - comment

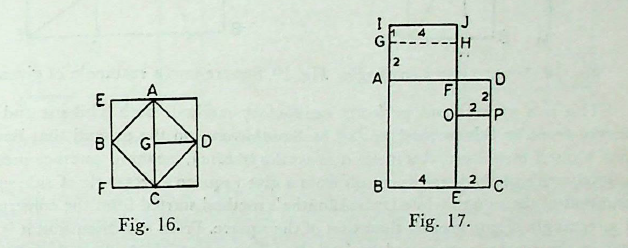

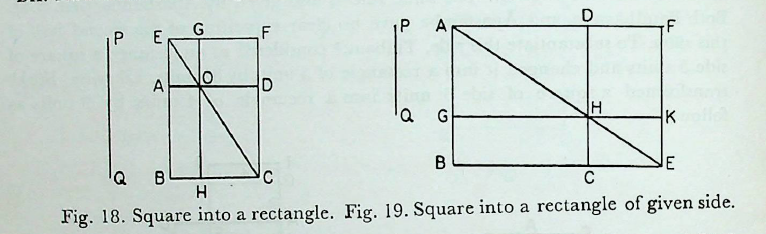

2.3-2.4. Baudhāyana has given two methods for transformation of a square into a rectangle.

According to the first method, a square is transformed into a rectangle, such that the diagonal of the square equals the longer side of the rectangle. The method is also given by Katyāyana (Kśl. 3.4).

The square ABCD is divided by its diagonal AC (Fig. 16). The portion ADC is again divided into two equal halves by GD and each is transferred to occupy the position AEB and BFC. Then AEFC is the required rectangle. For,

sq. \(ABCD = tr. ABC tr. AGD + tr. GCD\)

\(= tr. ABC + tr. AEB + tr. BFC\)

\(= rect. AEFC.\)

The method is limited in scope, for it only turns a square into a rectangle, the longer side of which is equal to the diagonal of the square.

The second method concerns the transformation of a square into a rectangle of which one side is given. The same rule is also given by Āpastamba (Aśl. 3.1). Both Baudhayana and Āpastamba gave no clear exposition of the second half of this sūtra. To substantiate this rule, Thibaut,4 considered as an instance a square of side 5 units and changed it into a rectangle of 3 units by \(8\frac{1}{3}\) units. Likewise, Bürk5 transformed a square of side 6 units into a rectangle of 4 units by 9 units as follows.

The sq. ABCD is broken into a rect. ABEF making its side BE ( 4 units) equal to the desired shorter side of the rectangle, and rectangle OECP (where EC = 2 units), together with a square FOPD. The rectangle OECP is transferred to the other side, and GAFH is its new position. Next the smaller square FOPD (2 units X 2 units) is changed into a rectangle (of 1 unit by 4 units) and IGHJ becomes its new position (Fig. 17). Hence BI ( \(6 + 2 + 1 = 9\) units) is the length of the new rectangle. Similarly, if we change a square of 7 units into a rectangle of 5 units by \(\frac{49}{5} (= 7 + 2 + \frac{4}{5})\) units, we have to construct a rectangle of unit by 5 units from a square of 2 units by 2 units. This is actually no solution to the problem since the transformation of square FOPD to a rectangle IGHJ is again a problem of fundamental nature.

The commentators Dvārakānātha Yajvā and Sundararāja have described a general method as follows: yāvadicchaṇ pārśvamānyau prācyau vardhayiṭvā uttarapūrvām karṇarajjumāyacchet sā dirgha caturaśramadhyasthāyām samacaturaśra tiryanmānyām yatra nipatati tata uttaraṁ hitvā dakṣiṇāṇsaṁ tiryanmānīm kuryāt taddirghacaturaśram bhavati| This means: Having increased upto the desired length the two sides (pārŝvamāni)

towards east, the diagonal-cord is stretched towards north-east corner. The (diago- nal) line cuts the breadth (tiryaṅmāni) of the square lying inside the rectangle; the northern portion is cut off (by drawing a line through this point parallel to prāci); the southern side becomes the breadth (tiryaṅmāni) of the (desired) rectangle.

In Fig. 18, the sides BA and CD of the square ABCD are increased to E and F respectively, so that each of the sides BE and CF becomes equal to the given length PQ. The diagonal cord CE cuts the side AD at O. Then the northern portion. EBHG is cut off by drawing a line HG passing through O parallel to the prăci line BA. Now GHCF is the required rectangle.

This is a general and perfectly satisfactory method. Both Thibaut and Bürk did not consider this method as that of Baudhāyana on the ground that Baudha- yana himself mentioned this method as anyaśca prakāraḥ, meaning ‘another method’. Baudhāyana’s method was to cut off from a given square a rectangle of side smaller than that of the square while Dvārakānātha’s method started from the construction of a rectangle of side greater than that of the square. From our discussion it is clear that in the methods suggested by both Baudhāyana and Dvārakānātha, the final result of constructing a rectangle equivalent to a square is the same but their methods of attaining it are different. For this difference, Sundararāja gave the same line of argument as that of Dvārakānātha in transforming a square into a rectangle with the remark, ayamatra prakāraḥ6 meaning, ’this is the method taught here’. To keep a symmetry with the original sūtra of Baudhāyana, Datta7 put the method of Dvåārakānātha in the following form.

From the square ABCD, the portion AGHD is cut off, such that \(AG = DH = PQ,\) the side of the required rectangle. The diagonal AH is produced to meet BC (produced) at E. The rectangle ABEF is completed. Then AGKF is the equivalent rectangle (Fig. 19).

For, tr. \(ABE = tr. AFE, tr. AGH = tr. ADH and tr. HCE = tr. HKE.\) Hence rectangle GC = rectangle DK.

Now sq. ABCD = rect. AH + rect. GC

=rect. AH + rect DK

=rect. AK.

मूलम्

अपि वै तस्मिंश्चतुरश्रं समस्य तस्य करण्यापच्छिद्य यदतिशिष्यते तदितरत्रोपदध्यात् ४

विश्वास-प्रस्तुतिः

दीर्घचतुरश्रं समचतुरश्रं चिकीर्षंस्तिर्यङ्मानीं करणीं कृत्वा शेषं द्वेधा विभज्य पार्श्वयोरुपदध्यात् । खण्डमावापेन तत्संपूरयेत् । तस्य निर्हार उक्तः ५

English

If it is desired to transform a rectangle into a square, its breadth is taken as the side of a square (and this square on the breadth is cut off from the rectangle). The remainder (of the rectangle) is divided into two equal parts and placed on two sides (one part on each). The empty space (in the corner) is filled up with a (square) piece. The removal of it (of the square piece from the square thus formed to get the required square) has been stated.

English - comment

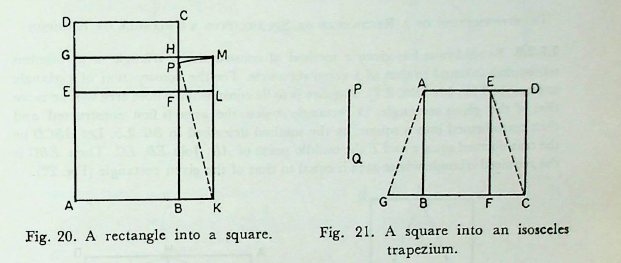

2.5. This is a most general method of transforming a rectangle into a square given by Baudhāyana. The same method is also taught by Āpastamba (Ãśl. 2.7) and Kātyāyana (Kśl. 3.2). Baudhāyana’s method runs as follows.

Let ABCD be the given rectangle (Fig. 20). The portion ABFE is cut off such that AE = AB = the breadth of the rectangle. The remaining portion EFCD is cut off into two equal halves. One half GHCD is placed on the other side and its new position becomes BKLF. A small square FLMH is fitted at the corner.

Now, rect. ABCD = sq. AKMG — sq. FLMH, which shows that the rectangle ABCD is expressed as the difference of two squares. Since the method of nirhāra has already been taught before by Baudhāyana (BŚl. 2.2), a square equal to the difference of the two squares mentioned above is found by allowing the side KM to fall at P over BH. Then the square on BP will be equal to the difference of two squares, which is equal to the area of the given rectangle.

For, \(BP^2 = PK^2 - BK^2\)

\(= MK^2 - FL^2\)

=sq. ABFE + rect. EFHG + rect. FBKL

=sq. ABFE + rect. EFHG + rect. DGHC

=rect. ABCD.

In the case of a rectangle of very great length, Kātyāyana’s (Kśl. 3.3) advice is to cut it again and again by its breadth, combine the pieces by the samāsa method (Bśl. 2.1) and finally to achieve the result by applying the nirhāra method (Bśl. 2.2). This is clearly no improvement upon the method given by Baudhāyana.

मूलम्

दीर्घचतुरश्रं समचतुरश्रं चिकीर्षंस्तिर्यङ्मानीं करणीं कृत्वा शेषं द्वेधा विभज्य पार्श्वयोरुपदध्यात् । खण्डमावापेन तत्संपूरयेत् । तस्य निर्हार उक्तः ५

विश्वास-प्रस्तुतिः

चतुरश्रमेकतोऽणिमच्चिकीर्षन्नणिमतः करणीं तिर्यङ्मानीं कृत्वा शेषमक्ष्णया विभज्य विपर्यस्येतरत्रोपद-ध्यात् ६

English

If it is desired to reduce one side of a square (that is, to make an isosceles trapezium) the reduced side is to be taken as the breadth (of a rectangular portion to be cut off from the square); the remaining part (of the square) is divided by the diagonal and (one half), after being inverted, is placed on the other side.

English - comment

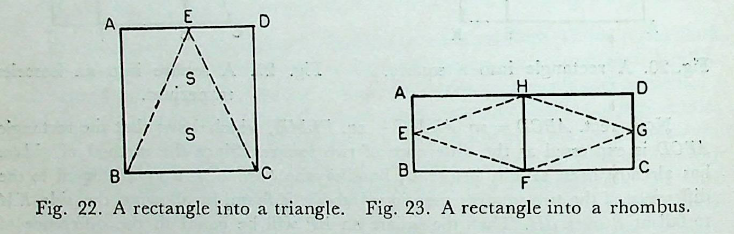

2.6. By this method a square as well as a rectangle are changed into a trapezium of given side (smaller than the side of the square).

The square ABCD is required to be transformed into an isosceles trapezium AGCE, whose shorter side AE is equal to the given length PQ (Fig. 21). The rectangular portion EFCD is divided into two equal halves and the half ECD is shifted to its other side, such the AGB is its new position. Hence AGCE is the required isosceles trapezium.

For, sq. \(ABCD = rect. ABFE + tr. EFC + tr. ECD\)

\(= rect. ABFE + tr. EFC + tr. AGB\)

=trap. AGCE

This method of transformation was known earlier in the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa (Śat. Br. 10.2.1.4).

मूलम्

चतुरश्रमेकतोऽणिमच्चिकीर्षन्नणिम-तः करणीं तिर्यङ्मानीं कृत्वा शेषमक्ष्णया विभज्य विपर्यस्येतरत्रोपद-ध्यात् ६

विश्वास-प्रस्तुतिः

चतुरश्रं प्रौगं चिकीर्षन्यावच्चिकीर्षेद्द्विस्तावतीं भूमिं समच-तुरश्रां कृत्वा पूर्वस्याः करण्याः मध्ये शङ्कुं निहन्यात् । तस्मिन्पाशौ प्रतिमुच्य दक्षिणोत्तरयोः श्रोण्योर्निपातयेत् । बहिस्पन्द्यमपच्छिन्द्यात् ७

English

If it is desired to transform a square into (an isosceles) triangle, the square whose area is to be so transformed is doubled and a pole fixed at the middle of its east side; two cords with their ties fastened to it (the pole) are stretched to south-western and north-western corners (of the square); portions lying outside the cords are cut off.

मूलम्

चतुरश्रं प्रौगं चिकीर्षन्यावच्चिकीर्षेद्द्विस्तावतीं भूमिं समच-तुरश्रां कृत्वा पूर्वस्याः करण्याः मध्ये शङ्कुं निहन्यात् । तस्मिन्पाशौ प्रतिमुच्य दक्षिणोत्तरयोः श्रोण्योर्निपातयेत् । बहिस्पन्द्यमपच्छिन्द्यात् ७

विश्वास-प्रस्तुतिः

चतुरश्रमुभयतः प्रौगं चिकीर्षन्यावच्चिकीर्षेद्द्विस्तावतीं भूमिं दीर्घ-चतुरश्रां कृत्वा पूर्वस्याः करण्याः मध्ये शङ्कुं निहन्यात् । तस्मिन्पा-शौ प्रतिमुच्य दक्षिणोत्तरयोर्मध्यदेशयोर्निपातयेत् । बहिःस्पन्द्यमप-च्छिन्द्यात् । एतेनापरं प्रौगं व्याख्यातम् ८

English

If it is desired to transform a square into a double (isosceles) triangle (that is, rhombus), a rectangle twice as large as the square to be so transformed is made; a pole is fixed at the middle of its east side; two cords with their ties fastened to it (the pole) are stretched to the middle points of the southern and northern side (of the rectangle); portions lying outside the cords are cut off; thereby the (isosceles) triangle on the other side is explained.

English

2.7-2.8. Baudhāyana has given a method of constructing a triangle or a rhombus whose area is equal to that of a given rectangle. For the construction of a triangle as described in sūtra (Bśl. 2.7), a square is to be constructed whose area will be twice that of the given rectangle. A rectangle twice the area is first constructed and then transformed into a square by the method described in B§l. 2.5. Let ABCD be the transformed square and E the middle point of AD. Join EB, EC. Then EBC is the required triangle whose area is equal to that of the given rectangle (Fig. 22).

For, tr. EBC = \(\frac{1}{2}\) sq. ABCD = given rectangle.

For the construction of a rhombus as in sūtra (Bśl. 2.8), let the rectangle ABCD be so constructed that its area is double that of the given rectangle. Let E, F, G, H be the middle points of AB, BC, CD and DA respectively. Join EF, FG, GH and HE to produce the required rhombus EFGH (Fig. 23).

For, rhombus EFHG

\(=tr. EFH + tr. GFH\)

\(= \frac{1}{2} (rect. ABFH+rect. CDHF)\)

\(=\frac{1}{2} rect. ABCD\)

This is given by both Apastamba (Asl. 12.8) and Kātyāyana (Kśl. 4.4).

मूलम्

चतुरश्रमुभयतः प्रौगं चिकीर्षन्यावच्चिकीर्षेद्द्विस्तावतीं भूमिं दीर्घ-चतुरश्रां कृत्वा पूर्वस्याः करण्याः मध्ये शङ्कुं निहन्यात् । तस्मिन्पा-शौ प्रतिमुच्य दक्षिणोत्तरयोर्मध्यदेशयोर्निपातयेत् । बहिःस्पन्द्यमप-च्छिन्द्यात् । एतेनापरं प्रौगं व्याख्यातम् ८

विश्वास-प्रस्तुतिः

चतुरश्रं मण्डलं चि-कीर्षन्नक्ष्णयार्धं मध्यात्प्राचीमभ्यापातयेत् । यदतिशिष्यते तस्य सह तृतीयेन मण्डलं परिलिखेत् ९

English

If it is desired to transform a square into a circle, (a cord of length) half the diagonal (of the square) is stretched from the centre to the east (a part of it lying outside the eastern side of the square); with one-third (of the part lying outside) added to the remainder (of the half diagonal), the (required) circle is drawn.

English

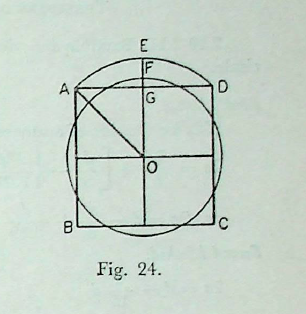

2.9. The following method of transforming a square into a circle is given by Baudhāyana. The same method has also been taught by Āpastamba (Ãśl. 3.2), Kātyāyana (Kśl. 3.11) and Mānava (Mśl. 1.8).

Let ABCD be the given square and O its centre. The half diagonal OA is drawn over the east-west line OE, such that OA OE. Then a circle with radius OF equal to OG plus of GE i.e. GF, is drawn to give the required circle (Fig. 24).

Here, radius \(= OF = OG + GF\)

\(= OG + \frac{1}{3}GE\)

\(= OG + \frac{1}{3} (OA - OG).\)

Let 2a be the side of the square ABCD.

OF = \(a + \frac{1}{3}(a\sqrt{2}-a)\)

\( r=a [1 + \frac{1}{3}(\sqrt{2}-1)]\) where OF = r

or \(r = \frac{a}{3} (2 + \sqrt{2})\)

As per Bśl 2.12 (vide infra), \(\sqrt{2}\) is given by,

\(\sqrt{2} = 1 + \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{3.4} - \frac{1}{3.4.34}\)

\(= \frac{577}{408} = 1.4142156\)

Baudhāyana’s more refined value of π is given by (Bśl. 4.15),

\(π = 4 (1 - \frac{1}{8} + \frac{1}{8.29} - \frac{1}{8.29.6} + \frac{1}{8.29.6.8})\)

= 3.0885.

Using the above value of \(\sqrt{2}\) and π, the area of the transformed circle = π r^2 = 3.9989a^2, which is in close agreement with the area of the given square, 4a^2.

If we take π = 3 (Bśl. 4.15), area of the circle becomes 3.885a^2, which falls far short of the area of the given square. Āpastamba made an additional remark on the method of circling a square as sānityā maṇḍalam yāvaddhiyate tāvadāgantu, which makes also the interpretation equally difficult as to whether, the method is exact or inexact one. The commentator Kapardisvāmī has broken up sānityā as sā and anityā concluding that the method is an inexact one. The passage has been interpreted by Karavindasvāmī as follows: “The circle is exactly as large as the square, for as much the circle falls short, so much comes in.8 Thibaut, Bürk and Datta have referred to the same difficulty as to the real sense in which these words were used by Āpastamba.9

However, Dvārakānātha Yajvā10, commentator of Baudhāyana sulba has proposed the following correction to the formula of Baudhāyana, which gives better result:

\(r = [a+ \frac{a}{3}(\sqrt{2} -1 )] (1- \frac{1}{118})\)

The problem of quadrature has also been discussed by Drenckhahn11 Chakrabarty,12 and Gurjar.13

मूलम्

चतुरश्रं मण्डलं चि-कीर्षन्नक्ष्णयार्धं मध्यात्प्राचीमभ्यापातयेत् । यदतिशिष्यते तस्य सह तृतीयेन मण्डलं परिलिखेत् ९

विश्वास-प्रस्तुतिः

मण्डलं चतुरश्रं चिकीर्षन्विष्कम्भम-ष्टौ भागान्कृत्वा भागमेकोनत्रिंशधा विभज्याष्टाविंशतिभागानुद्धरेत् । भागस्य च षष्ठमष्टमभागोनम् १०

English

To transform a circle into a square, the diameter is divided into eight parts; one (such) part after being divided into twentynine parts is reduced by twentyeight of them and further by the sixth (of the part left) less the eighth (of the sixth part).

मूलम्

मण्डलं चतुरश्रं चिकीर्षन्विष्कम्भम-ष्टौ भागान्कृत्वा भागमेकोनत्रिंशधा विभज्याष्टाविंशतिभागानुद्धरेत् । भागस्य च षष्ठमष्टमभागोनम् १०

विश्वास-प्रस्तुतिः

अपि वा पञ्चदशभागान्कृत्वा द्वा-वुद्धरेत् । सैषानित्या चतुरश्रकरणी ११

English

Alternatively, divide (the diameter) into fifteen parts and reduce it by two of them; this gives the approximate side of the square (desired).

English

2.10-2.11. Baudhāyana describes two methods of finding quadrature of a circle.

First Method.

If 2a be the side of a square and d the diameter of the circle, then

\(2a = \frac{7d}{8} + [\frac{d}{8}- {\frac{28d}{8.29} + (\frac{d}{8.29.6} - \frac{d}{8.29.6.8})}]\)

or, \(2a = d - {d}{8} - \frac{d}{8.29} - \frac{d}{8.29} (\frac{1}{6} - \frac{1}{6.8})\)

Second Method.

\(2a = d - \frac{2}{15}d\)

This result is also given by both Āpastamba (Āśl. 3.3) and Kātyāyana (Kśl.

Rationale.

(A) The rationale of the result obtained from the first method is given by Thi- baut, Cantor and Müller as follows:

(i) Thibautd14 has suggested that the result was possibly obtained from the previous result of circling a square, \(r = \frac{a}{3} (2 + \sqrt{2})\) by inversion.

For, \(2a = \frac{3}{2+\sqrt{2}}d\)

\(= \frac{1224}{1393}\)

:: \(\sqrt{2} = \frac{577}{408}\)

\(= d (\frac{7}{8} + \frac{1}{8.29} \frac{1}{8.29.6} + \frac{1}{8.29.6.8})\)

since, 1) 1/8th of 1393 = \(174\frac{1}{8}\)

- 7/8th of 1393 = \(1218\frac{7}{8}\)

(less by \(5\frac{1}{8}\) from 1224)

-

\(\frac{1}{8.29}th of 1393 = 6\) (approx)

-

\(\frac{1}{8.29.6}th of 1393 = 1\)

-

\(\frac{1}{8.29}th of 1393 =\frac{1}{8}\)

(i.e. \(6 - 1 + \frac{1}{8} = 5\frac{1}{8}\) surplus by \(5\frac{1}{8}\) from 1224)

More or less the same method is given by Cantor.15

(ii) Müller’s derivation16 is as follows:

\(2a = - \frac{3}{2+\sqrt2}d= \frac{3\sqrt{2}}{2\sqrt{2}+2}d= \frac{3}{2}. \frac{\sqrt{2}}{1+\sqrt{2}}d\)

= \(\left(\frac{3}{2}.\frac{17-\frac{1}{34}} {29-\frac{1}{34}}\right) d=\left(\frac{51-\frac{3}{34}}{58-\frac{2}{34}}\right)d\) \(\because \sqrt{2}= \frac{17}{12} - \frac{1}{12.34}\)

= \(\left(1-\frac{7+\frac{1}{34}} {58-\frac{2}{34}}\right)d\)

= \(d-\frac{1}{8}. \left(\frac{56+\frac{8}{34}} {58-\frac{2}{34}}\right) d = d -\frac{1}{8} \left[1-\frac{2-\frac{10}{34}}{58-\frac{2}{34}}\right]d\)

= \(d-\frac{1}{8}\left[1-\frac{1}{29}\left(1-\frac{\frac{10}{34}-\frac{2}{34.29}}{2-\frac{2}{34.29}}\right)\right]\)

= \(d-\frac{1}{8}d\left[1-\frac{1}{29}\left{ {{1-\frac{1}{6}(1-\frac{4+\frac{5}{29}} {34-\frac{1}{29}})}} \right}\right]\)

= \(d-\frac{1}{8}d+ \frac{1}{8.29}d \left[ 1-\frac{1}{6} \left{1\frac{1}{8}\left(1-\frac{2-\frac{41}{29}} {34-\frac{1}{29}}\right) \right}\right]\)

thus,

\(2a = d - \frac{d}{8}+ \frac{d}{8.29} - \frac{d}{8.29}(\frac{1}{6} - \frac{1}{6.8})- \frac{d}{8.29.6.8}.\frac{2-\frac{41}{29}} {34-\frac{1}{29}}\)

The last term is neglected, it being very small.

However, Dvārakānātha17 has suggested a more correct result of the above formula as follows:

\(2a= \left[d-\frac{d}{8} + \frac{d}{8.29} - \frac{d}{8.29} \left( \frac{1}{6} -\frac{1}{6.8} \right)\right] \times\left(1+\frac{1}{2}. \frac{3}{133} \right)\)

(B) The rationale of the second method may be obtained as follows:

The average of two squares, one circumscribed and the other inscribed, determines the approximate area of the circle.

\(\therefore Area of the circle = \frac{4r^2 + 2r^2}{2} =3r^2\)

Since the square is taken to be equal in area to the circle,

4a^2 = 3r^2

or \(a = \frac{\sqrt{3}} {2}r\)

The value of √3 may be obtained by the method of successive approximation as follows:

(i) \(\sqrt{A} = \sqrt{a^2 + c} = a + \frac{c}{2a+1},\)

where 2a + 1 is the difference between the squares of c and the next positive integer. Therefore,

\(\sqrt{3} = \sqrt{1^2+2} = 1 + \frac{2}{3} = \frac{5}{3}\)

(ii) For finding the next approximation e, \(\sqrt{A}\) is written as

\(\sqrt{A} = a + \frac{e}{2a+1}+e\)

Then squaring both sides and cancelling the value of e^2, since it is very small, the value of e is obtained. Here \(\sqrt{3} = \frac{5}{3}+e\)

Squaring and cancelling the value of e^2 we get

\(\frac{10}{3}e+\frac{25}{9}=3\)

or e = \(frac{1}{15}\)

then \(\sqrt{3} = 1 + \frac{2}{3}+ \frac{1}{15} = \frac{26}{15}\)

Obviously,

\(a=\frac{1}{2}.\sqrt{3}r=\frac{1}{2}.\frac{26}{15}r=\frac{13}{15}r\)

= \(r-\frac{2}{15}r\) [r = radius]

or \(2 a = d - \frac{2d}{15}\)

[ d = 2r = diameter]

The value of \(\sqrt{2}\)

मूलम्

अपि वा पञ्चदशभागान्कृत्वा द्वा-वुद्धरेत् । सैषानित्या चतुरश्रकरणी ११

विश्वास-प्रस्तुतिः

प्रमाणं तृतीयेन वर्धयेत्तच्च चतुर्थेनात्मचतुस्त्रिंशोनेन । सविशेषः १२

English

The measure is to be increased by its third and this (third) again by its own fourth less the thirtyfourth part (of that fourth); this is (the value of) the diagonal of a square (whose side is the measure).

English

2.12 The value of \(\sqrt{2}\) given by Baudhayana is

\(\sqrt{2}=1+\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{3.4}-\frac{1}{3.4.34}\) (approx)

The same sūtra is also given by Āpastamba (Ãśl. 1.6) and Kâtyāyana (Kśl. 2.9).

In decimal fraction, the above value of \(\sqrt{2} = 1.4142156.\) According to modern calculation, \(\sqrt{2} = 1.4142135.\) 4142135. Thus it is clear that the ancient Indians attained a remarkable degree of accuracy in calculating an approximate value of \(\sqrt{2}.\) The śulbakāras gave methods, for constructing a square equal to the sum of two equal squares, but gave no method of calculating the value of its diagonal.

Thibaut, Rodet, Datta, and others gave possible methods of solution for arri- ving at the value as follows:-

(i) Thibaut’s proof.18

Now, \(17^2 = 2.12^2 — 1\). Thibaut argued, by how much the side 17 must be diminished in order that the square on it may be 2.12^2 exactly. Since \(2 \times 17 \times \frac{1}{34}=1\) , he observed, two strips each of \(\frac{1}{34}\) (approximately) are to be cut off from a square with 17 as side to obtain the square 2.12^2 (i.e. \(12^2 + 12^2\) ).

Hence, \(\left(17-\frac{1}{34}\right)^2 = 2.12\)

or, \(\frac{17-\frac{1}{34}} {12}= \sqrt{2}\)

Again, \(17 - \frac{1}{34} = 12 +4+1-\frac{1}{34}\)

\(17 - \frac{1}{34} = 12 \left(1+\frac{1}{3} +\frac{1}{3.4} - \frac{1}{3.4.34}\right)\)

or, \(\frac{17-\frac{1}{34}} {12}=1+\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{3.4}-\frac{1}{3.4.34}\)

or, \(\sqert{2} = 1+\frac{1}{3}+ \frac{1}{2.4} - \frac{1}{3.4.34}\)

In Baudhāyana’s selection of units of 12 angulas (= 1 pada) and 34 tilas (=1 aṅgula) Thibaut found justification for the choice of the arbitrary relation 17^2 = 2.12^2 (approx.) leading to the origin of the formula of √2, as given in the text.

(ii) Rodet’s approximation.19

According to Rodet, the approximation adopted by śulbakāras may be obtained by successive approximation.

\(\sqrt{a^2+r}= a+\frac{r}{2a+1}+ \frac{\frac{r}{2a +1}(1-\frac{r}{2a+1})}{2(1+\frac{r}{2a+1})}+e\)

where e is a fourth term approximation. Rodet might have obtained the result as follows:

\(\sqrt{a^2 + r} = a + \frac{r}{2a+1}\)

[two term approximation] where 2a + 1 is the difference of the squares of a and the next positive integer a + 1. For third term approximation, assume

\(\sqrt{a^2 + r} = a + \frac{r}{2a+1}+e_{1}\)

\(= \frac{2a+r+1} {2a+1}+ e_{1}\)

Squaring and neglecting \(e\frac{2}{1}\), we get

\(\frac{2(2a+r+1)}{2a+1}e_1= a^2+r-\left(\frac{2a+r+1}{2a+1}\right)\)

\(=\frac{r(2a+1-r)}{(2a+1)^2}\)

\( \therefore e_{1}=\frac{r(2a+1-r)}{2(2a+1) (2a+1+r)}\)

\(=\frac{\frac{r}{2a+1}(1-\frac{r}{2a+1})}{2(1+\frac{r}{2a+1})}\)

Likewise, the fourth term approximation is obtained. Obviously, following above, we write,

\(\sqrt{2} = \sqrt{1^2 + 1} = 1+ \frac{1}{3}\)

Let \(\sqrt{2} = 1 + \frac{1}{3} + e = \frac{4}{3}+e\)

Squaring both sides and cancelling e^2 from both sides, we get

\(\frac{8}{3}e=2-\frac{16}{9}=\frac{2}{9}\)

\(\therefore e=\frac{2}{9}\times \frac{3}{8}=\frac{1}{12}=\frac{1}{3.4}\)

\(\therefore \sqrt{2} = 1+\frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{3.4}\)

Let \(\sqrt{2} = 1+\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{3.4}+ e\)

\(=\frac{17}{12}+e\)

Squaring both sides and cancelling e^2 from both sides,

\(\frac{17}{6}e=2-\left(\frac{17}{12}\right)^2= -\frac{1}{144}\)

\(\therefore = - \frac{1}{144}\times\frac{6}{17}=\frac{1}{12.34}\)

\(=-\frac{1}{3.4.34}\)

\(\therefore \sqrt{2} = 1+\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{3.4}-\frac{1}{3.4.34}\) (approx.)

The methods described later by Gurjar20 and Gupta21 are the same and no improvement over Rodet’s method.

(iii) Datta’s proof.22

Datta’s proof is an improvement over that of Thibaut and maintains the method of construction followed in the śulba.

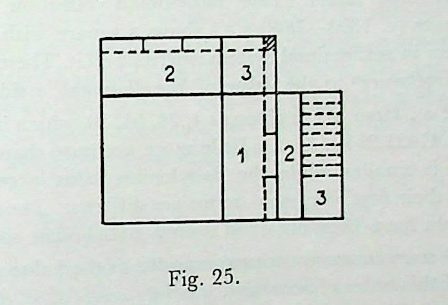

The method consists in constructing a square with area equal to the sum of the areas of the two other squares having sides of one unit in length (Fig.. 25).

For this one of the two squares having side of unit length is divided into three equal parts by lines drawn parallel to one of its sides. Each of these parts forms a rectangular piece of one unit in length and one-third unit in width. Two of these rectangular parts are then joined length-wise to the two adjacent sides of the other unit square. This leaves a square hole at one of the corners of the enlarged unit square.

This square hole will have a side of one-third unit in length. The remaining rectangular piece of the divided unit square is again subdivided into three equal parts each forming a square of side one-third unit in length. One of the squares is fitted into the square hole mentioned above. Each of the remaining two squares is again subdivided into four equal rectangular pieces having length of \(\frac{1}{3}\) unit and width of \(\frac{1}{3.4}\) unit. Eight of these small rectangular pieces are placed length-wise side by side on the two adjacent sides of the enlarged square with four on each side. This again leaves a square hole at the corner having a side of length \(\frac{1}{3.4}\) unit.

Now two equal strips have to be deducted from the two adjacent sides of the enlarged square under construction; the width of each of the strips is therefore given by

\(\frac{(\frac{1}{3.4})^2}{2\times (1+\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{3.4})}=\frac{1}{3.4.34}\)

Hence \(\srt{2}\), the side of the desired square is given approximately by

\(1+\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{3.4}-\frac{1}{3.4.34}\)

Value of \(\sqrt{2}\) in other culture areas.

A small cuneiform tablet (Yale Babylonian collection No. 7289) of the old Babylonian times (c. 1800–1600 B.C.) shows a square with its two diagonals, with three numbers in sexagesimal system inscribed on it. These three numbers are interpreted by Neugebauer23 as the value of the diagonal, a side and the value of \(\sqrt{2}\) (since d = \(\sqrt{2}\) a). Here \(\sqrt{2}\) is given as 1, 24, 51, 10, which in terms of decimals comes out to be 1.41421,291……….” a little more accurate than the Indian value. The Indian value is smaller while the Babylonian value larger than the actual value. Moreover, their first fractional terms are different. The suggestion that the Indian value might have been obtained from a Babylonian source is groundless. As regards Greek24 sources, many approximations to the value of \(\sqrt{2}\) are known, but not a value of this order of accuracy.

Irrationality of \(\sqrt{2}\).

Baudhāyana, Āpastamba and Kātyāyana gave the value of \(\sqrt{2}\), as mentioned above, with an additional term viśeșa (approximate). Many scholars expressed doubt whether, by the term viseṣa, the śulbakāras recognized the irrationality of \(\sqrt{2}\). According to Karavindasvāmī,25 a commentator on the Āpastambaśulbasūtra, the root sis when prefixed by vi denotes in all cases a ‘correction in excess’. Datta26 has discussed the matter in detail, and the commentator can be relied upon in this interpretation. Looking into the ancient literature of India, we find in the early canonical works of the Jainas many instances of the employment of the term viśeṣa in the same connection as we find in the śulba. A few instances are given here.

(i) The diameter of the circle is 99640 yojanas, the circumference is 315089 and a little over (kiñcid-viśeṣādhika) (Sūrya-prajñapati, sūtra 20).

(ii) The diameter is 100000 yojanas, circumference is 316227 yojanas 3 gavyutis 128 dhanus \(13\frac{1}{2}\) aṅgulas and a little over (kiñchid-viseṣādhika) (Jambūdvīpa-prajñapti, sūtra 3).

Hence viseșa refers to a small quantity, which is either in excess or in deficit, and cannot be accurately determined. Śulbakāras gave no proof for it, since it was beyond their tradition.

मूलम्

प्रमाणं तृतीयेन वर्धयेत्तच्च चतुर्थेनात्मचतुस्त्रिंशोनेन । सविशेषः १२

-

Aśl. Mysore 73, 39. ↩︎

-

Datta (2), 77. ↩︎

-

Datta (2), 79. ↩︎

-

Thibaut (1), 246. ↩︎

-

Bürk, 56, 334. ↩︎

-

Asl. Mysore 49. ↩︎

-

Datta (2), 90. ↩︎

-

Āśl. Mysore, 50. ↩︎

-

Datta (2), 142-43. ↩︎

-

Thibaut (2), 10, 21. ↩︎

-

Drenckhahn, 1-13. ↩︎

-

Chakrabarty (2), 23-28. ↩︎

-

Gurjar (2), 11-16. ↩︎

-

Thibaut (1), 254. ↩︎

-

Datta (2), 145. ↩︎

-

Müller, 201. ↩︎

-

Thibaut (2), 10, 21. ↩︎

-

Thibaut (1) 239-41 ↩︎

-

Rodet, 162-165 ↩︎

-

Gurjar (1), 6-10. ↩︎

-

Gupta, 77-79. ↩︎

-

Datta (2), 192-94. ↩︎

-

Neugebauer, 34, vide also Plate 6a. ↩︎

-

Heath (2), 155. ↩︎

-

Āśl., Mysore 73. ↩︎

-

Datta (2), 198-202. ↩︎