Source: TW

From 2011-07

Just Another Cassandra?

If you haven’t seen the basic biographical sketch, see that first… By the way, this was written in 2011—early in my journey.

I view myself as intrinsically optimistic, so I am unsettled by my growing concerns about the viability of our future—such worrying is not consistent with who I am. I will let posts speak to the nature of my concerns. Here, I paint a picture of my characteristic approach to life outside the energy/growth domain. I would consider all of this to be irrelevant personal detail except for the fact that by sharing it, my thoughts on energy/growth might have greater impact.

Fundamentally, I am a scientist and an explorer who loves to design and build things—especially things that collect exquisite, never-before-seen data.

I like creating from scratch, without relying heavily on studies of how similar devices/techniques have been approached by others before. The advantage to this style is that I am not as encumbered by outdated methods, at the expense of sometimes re-inventing the wheel. But what the heck: it’s fun!

A Track Record of Optimism

In high school, I built a 10-inch telescope, learning to machine parts for it.

In college, I soaked up lab experiences and racked up a number of formative research victories.

As a PhD student in physics at Caltech, I set my sights on building the first-ever cryogenic integral field spectrograph, installing it on the venerable Palomar 200-inch telescope (a step up from my 10-inch!), and using it to disentangle the train wrecks of merging galaxies.

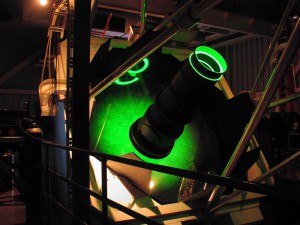

After graduate school, I started an ambitious project to test General Relativity by laser-ranging to the reflectors left on the Moon by the Apollo astronauts. Now achieving one-millimeter range precision, this system—much of which I designed and built—is a complex machine comprising a 500-pound laser, cutting-edge detectors (commercially unavailable), and picosecond-level timing electronics.

Outside my professional track, I have built a beautiful cedar-strip kayak,

a stand-alone photovoltaic system to power most of my home’s electricity needs,

and a water-catchment system employing a solar-pumped head tank.

Laser light bathing the 3.5 meter aperture of the Apache Point Observatory telescope, on its way to the moon.

Completed kayak ready for launch in La Jolla.

These accomplishments demonstrate that

I adopt an optimistic approach to challenges.

I assess the requirements of a project against resources available,

applicable state-of-the art technologies, and potential scientific gain.

In all cases, there are still huge uncertainties before committing:

problems that do not yet have a solution and could turn into showstoppers.

Too many of these will scare me away from attempting a project,

but there are always some at the start,

requiring optimism, confidence, and persistent dedication to overcome the challenges and find success.

And Occasionally, Not…

I have also learned that I am capable of seeing downsides when many around me do not.

I sold my San Diego house in early 2006 in reaction to fear that the market would crash.

I based this assessment on various pieces of quantitative information I had read:

that 60% of new home loans in the area were interest-only deals or other sub-prime shenanigans;

and that only 9% of San Diego families could afford the median home price.

Together with a raft of similarly ominous facts,

I could not any longer believe the articles—in the majority—claiming that the desirability of San Diego

would prevent any serious downfall in house prices.

This was not a bubble, many articles proclaimed,

but a new state of prosperity and a new normal.

It simply did not make sense to me.

But the pessimism that led to that decision is not a constant of my nature.

I was, after all, eager to get into the booming housing market when I moved to San Diego in 2003.

And I got back into the housing market in mid 2009 when it looked like San Diego may have hit its bottom.

The jury is still out on whether my re-entry was a good move, but hey—I’m optimistic!

I should also point out that I didn’t waste a moment’s time worrying about dire Y2K prognostications (largely because the issue was receiving enough attention).

In other words, I’m not generally attracted to doom scenarios.

All of these traits add to my worry about peak oil and related future challenges.

I’m scaring myself, in other words.

It reminds me of my reaction to the movie Titanic from 1997.

I spent some time afterwards thinking about what I would have done to save myself and a loved one.

I figured,

“I’m a smart, resourceful, situationally aware guy—surely my guile can get me out of difficult situations.”

But I couldn’t get over the fact that the chaos and powerful forces beyond my control could overwhelm any clever arrangements I might prepare in the few hours before the ship violently sank into the sea.

Sanity Check

Maybe I’m overreacting.

Maybe I’ve “flipped a bit,” as they would say in the world of computer engineering. But I keep evaluating this possibility and keep coming back to the fundamental and quantitatively convincing case: we have built a life of growth and prosperity based on a finite and soon-to-max-out resource with no equal replacement in sight.

This is uncharted territory,

and the fact that generations have experienced the fossil-fueled upswing

holds no predictive power over our future.

Just because growth has been thematic does not mean it will always be so.

The failure of most people to treat this possibility seriously is disheartening,

because it prevents meaningful planning for a different future.

We can all hope for new technologies to help us.

But this problem is too big to rely on hope alone,

and in any case, no practical technology can keep growth going indefinitely.

I want to be clear that

just because I am pointing out potential failure modes of our human endeavors

does not mean that I am predicting a dismal future.

It is clear to me that this can be avoided.

I’ll have to describe my rosy picture of the future in a post sometime.

The point of this blog is that

we have to apply scientific skepticism to our lofty narratives

so we aren’t misled down a false garden path.

(Aside: my wife’s colleague had a much more satisfying and sinister-sounding way to pronounce “misled,” sounding like my-zeld.)

Meanwhile, I lead a successful science experiment,

have an excellent track record for securing funding to carry out my research interests,

and am a tenured professor at a top research university

with excellent prospects for continued scientific success.

The easy path for me would be to ignore the worries

and continue taking advantage of a dream job with toys.

But I can’t shake the sense that we ignore this problem at our peril,

and that my scientific successes will be meaningless

in a world that loses its ability to maintain a high-tech existence.

I have to vie for a better outcome.