Source: here.

MM #7: Ecological Nosedive

This is the seventh of 18 installments in the Metastatic Modernity video series (see launch announcement), putting the meta-crisis in perspective as a cancerous disease afflicting humanity and the greater community of life on Earth. This episode will try (and probably fail) to convey the degree to which Earth’s biodiversity and ecological health are in peril.

As is the custom for the series, I provide a stand-alone companion piece in written form (not a transcript) so that the key ideas may be absorbed by a different channel. The write-up that follows is arranged according to “chapters” in the video, navigable via links in the YouTube description field.

Introduction

This is the usual short naming of the series, of myself, and the topic of this episode (the ecological nosedive) as part of the process for putting modernity into context.

Reminder: One of Many

As covered in previous episodes, humans are one of approximately 10 million living species on the planet. We are all in this together. Humans are not the pinnacle of evolution, but one of millions of temporary twig-ends. While we have become the dominant influence in nearly every ecological setting, we are not a keystone species acting as an anchor for biodiversity—rather the opposite, of late.

Mammal Mass-Acre

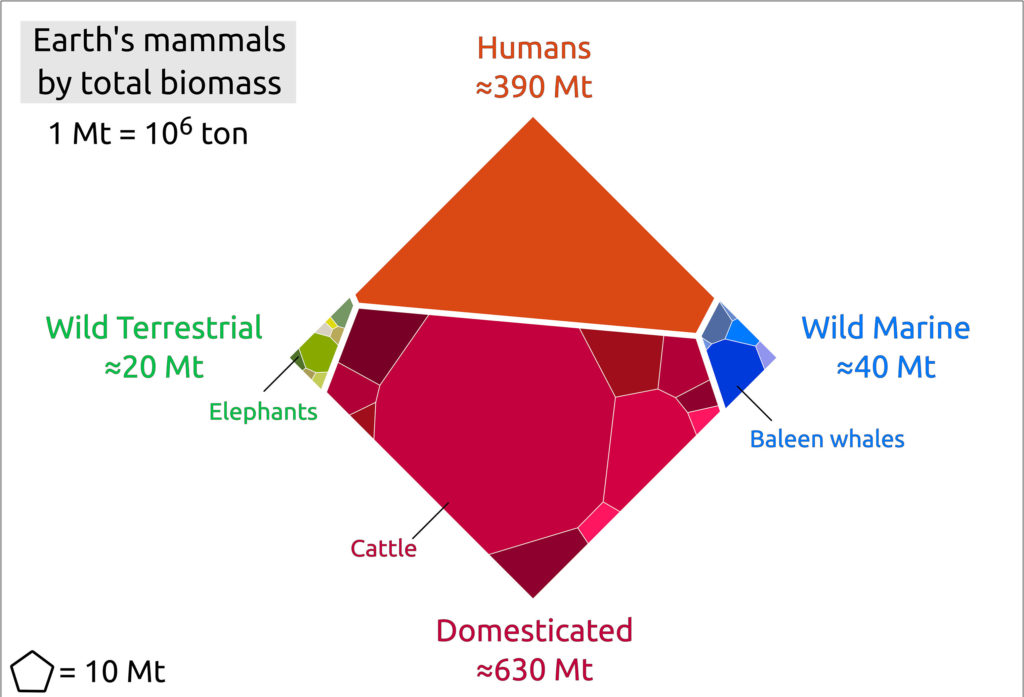

Humans and our domesticated animals have expanded to about 95% of all mammal mass on the planet. The wild mammals are really squeezed into the corners, in the graphic below. Wild land mammals are now down to 2% of the total, and falling fast!

The following is not a serving suggestion, or even the way ecology works, but provided for reference: if all of the approximately 5,000 mammal species on the planet had an equal share of mammal biomass, the human population would number 4 million. This gives a crude sense for the present degree of human imbalance (2,000 times the equipartition number). Ten thousand years ago, humans were indeed close to an equal share of mammal biomass, by species.

Today, wild land mammals total 20 megatons (wet mass). Some quick math reveals that spreading this mass over 8 billion people results in 2.5 kilograms (5.5 lbs) of wild mammal mass per person on the planet. That’s tiny: smaller than most house cats. Think about that: your “allocation” of wild land mammal mass on the planet would fit in a purse! Talk about vulnerable!

Here is a zoom-in of how the wild mammal masses are distributed, in case you’re interested.

Cliff Edge, Revealed

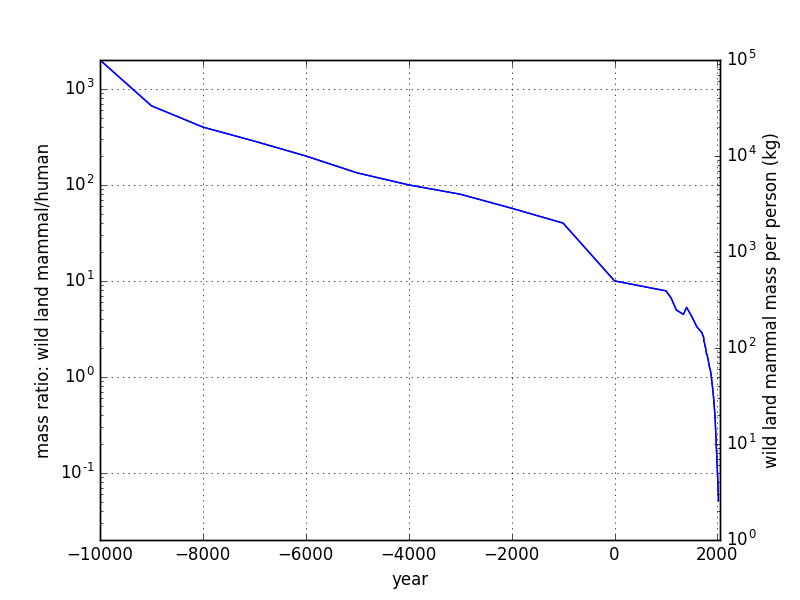

As indicated by the math above (and first presented in an earlier post), we now have 2.5 kg of wild land mammal mass per human. The plot below shows how this figure has evolved over time, on a logarithmic scale. Hint: it only recently went as low as 2.5 kg and is falling very fast!

If I had used a linear scale (going from zero to 2,000 on the left axis), the entire right-hand edge—the last 2,000 years—would be practically invisible, hugging the zero axis at less than 0.5% of full-scale! When a curve looks like a cliff edge on a logarithmic plot, that’s serious trouble!

Prior to agriculture, wild land mammal mass was over 1,000 times that of humans. By 1880, the mass of one species (humans) matched that of the entire menagerie of wild land mammals—on its way to the abyss. This is the cliff edge. This is the ecological nosedive. I think it’s worth a bit more than a shrug. I think every living human ought to internalize this fact, and make sure everyone they know is clued in as well.

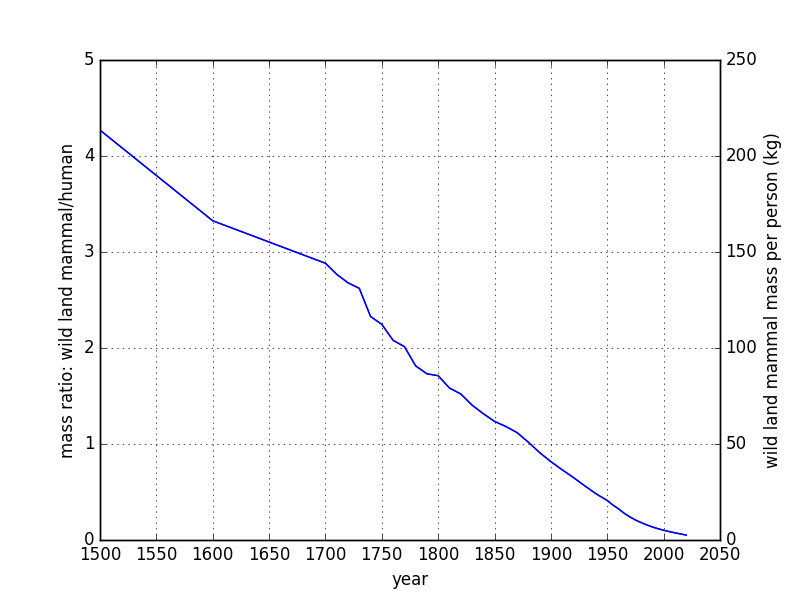

Linear Zoom

The linear-scale zoom-in above emphasizes that on a per-person basis, wild land mammals are almost gone. To be sure, a huge part of this story is the swelling of human population, but unmistakably accompanied by a dramatic reduction in land mammal mass, which has fallen to 30% of its already-suffering 1900 level. I don’t know. If we got rid of 70% in a little over a century, do you think we are capable of finishing the job?

In Other News

I focus on mammals partly because that’s what we are, and the animals to whom we most strongly identify. But the losses are across the board. Insects are declining at 1–2% per year, as are birds and fish. Now, that may not sound very large, but the result adds up and translates to a loss of about three-quarters every century. We’ve done one century like that already. Another would put us below 10% of the 1900 populations (which were already down by then). At some point, sub-critical populations struggle, falter, and wink out—through no fault of their own.

Insects are foundational to ecology: food base, pollination, soil service, nutrient dispersal. Their loss can lead to cascading losses among other animals, which is part of what explains bird declines.

About 50 years ago, the Living Planet Index started tracking tens of thousands of vertebrate (mammal, bird, reptile, fish, amphibian) populations, finding an average population decline of 69% since 1970. That’s a huge problem.

Population declines are a necessary phenomenon on any path toward extinction. And indeed, extinction rates are up 100 to 1,000 times the background rate—and climbing.

Ecological resilience can only be pushed so far before cascading failures pile on as the web of life is shredded and its countless crucial interdependencies rendered inoperative.

A Sixth Mass Extinction

The scale and rapidity of these changes create credible concern that we are witnessing (causing) the beginning of a sixth mass extinction.

Earth has been slapped hard, out of nowhere, at alarming speed. Although the evidence of its reeling is all around us, it is far too soon to appreciate the severity of what we have set in motion. A hard slap on the face looks red in the moment, but later appears bruised and might turn into a black eye. We are currently only seeing the instant, real-time response and not the protracted bruising to follow, which will take a long time to play out as many wild populations glide toward extinction and domino-effect failures pile up.

Now, in case your temptation is to get smug about this (stupid animals: who needs them?), please take to heart the lesson from prior episodes in this series: it is a narrow fallacy to think of ourselves as being somehow separate from an ecological context. Ecological collapse is extremely dangerous to large, complex, hungry, high-maintenance animals like humans. We are not likely to fare well in a sixth mass extinction of our own making.

Even if one’s only concern is for one’s own survival, or that of one’s family, or even humans as a whole (although I sure hope anyone can see value in the more-than-human biodiverse world), I hope it is clear that it is also in one’s selfish interest not to destroy the basis of complex life on this planet. I stress again that we are not separate from, above, or transcendent beyond our extended living family. That seems to be the default and utterly foolish notion pervading our culture, based on a brief fireworks show of excessive and unsustainable inheritance-spending that is in the process of setting up catastrophic failure—and for more than just humans.

Causes

What’s causing all this to happen? The short answer is: modernity. Broken down, it’s a long list, but pretty predictable, actually.

- Deforestation 2. Habitat loss and fragmentation 3. Mining, manufacturing, associated pollution and waste 4. Over-fishing; over-hunting 5. Pesticide; herbicide; ecocide 6. Human-introduced invasive species (including domestic animals and plants) 7. Infrastructure encounters (e.g., roadkill, windows, turbines of all sorts) 8. Ocean acidification from CO₂, impairing shell formation 9. Climate change from anthropogenic CO₂

The last item on the list tends to attract most of the recent attention (because it threatens the market economy, too). Climate change is a serious issue, and indeed interacts with some of the others to exacerbate the problem. For instance, habitat fragmentation prevents many species—including plants via seed dispersal—from being able to migrate to new areas as conditions change.

Climate change is not the root cause of our ecological nosedive, which has been on a steady march since long before climate change reared its head. But it is on the list, and can be understood as yet another symptom of the underlying disease (modernity). It is important to realize that if we somehow eliminated climate change today—and wouldn’t that be nice—we would still be in deep trouble, ecologically speaking. Almost all the items on the list above remain in full force without the climate change wrinkle. Which major activities of modernity are meant to cease under solar panels, for instance? Isn’t the whole point of them to keep modernity fully powered and going about its usual business?

Gallery

I end this episode with a sequence of still captures (with permission) from a film by Jeff Gibbs called Planet of the Humans, which I recommend. The whole documentary can be seen on YouTube, but the closing scene is where these clips come from. Actually, the conclusions Gibbs reaches just before this are also very well put and worth a watch.

The final scene shows the process and effects of deforestation, specifically on orangutans. It’s truly hard to watch. I am still scarred, over a year after I first saw it. A mud-caked orangutan youth (precious sweet bean!) is struggling to get out of a ditch. If you watch closely, you can see what looks to me like a fit of frustration after failing to get a handhold on the crumbling bank. She’s in a bad way. She’s at wit’s end. Her whole world—the life-sustaining rain forest—has been utterly destroyed. She did nothing wrong, but didn’t stand a chance. As she lies dying, a combination of shock and resignation appear to shape her expression.

Yes, this is just one scene, and may be defensively labeled as one scary anecdote. But deforestation is global and massive in scale. How else do you think we got down to 2.5 kg of wild land mammal mass per human? Modernity’s ravenous maw gobbles “worthless” (in a market sense) ecological communities without a second thought.

We need to provide that second thought. Step one is to no longer cheer for modernity. Stop prioritizing whatever comfort humans crave at any expense. The costs of modernity are enormous and unavoidable, ultimately hurting us all. I’ll have a future episode on how we can’t just jettison the bad parts.

Closing and Do the Math

It’s hard to move on from such heart-wrenching images. But, we need to understand the severity of modernity’s damage to the community of life—which we constantly forget includes us.

The next episode will package various perspectives to help illustrate the ridiculous timeline of modernity, and how frighteningly rapid this discontinuity is.

As always, I end with an appeal to check out the companion write-up (e.g., on Do the Math), which you are already doing!

Views: 1015