Source: TW

Thank you for asking this! My PhD thesis is on prehistoric ecological change in the eastern Levant, so I could talk about this all day, but since you’ve already got two good answers and I’ve already spent too much time replying to them, I’ll have to try and keep this short. (Try.)

The Fertile Crescent

The first thing to consider is that the Middle East is huge and very geographically diverse. Our image of it in the West tends to be fixated on the desert. And a lot of it is desert. There are scrubby deserts, weird rocky deserts, and proper sandy deserts. But there are also snowy mountains in Iran, lakes in Turkey, marshes in Iraq and forests in Lebanon.

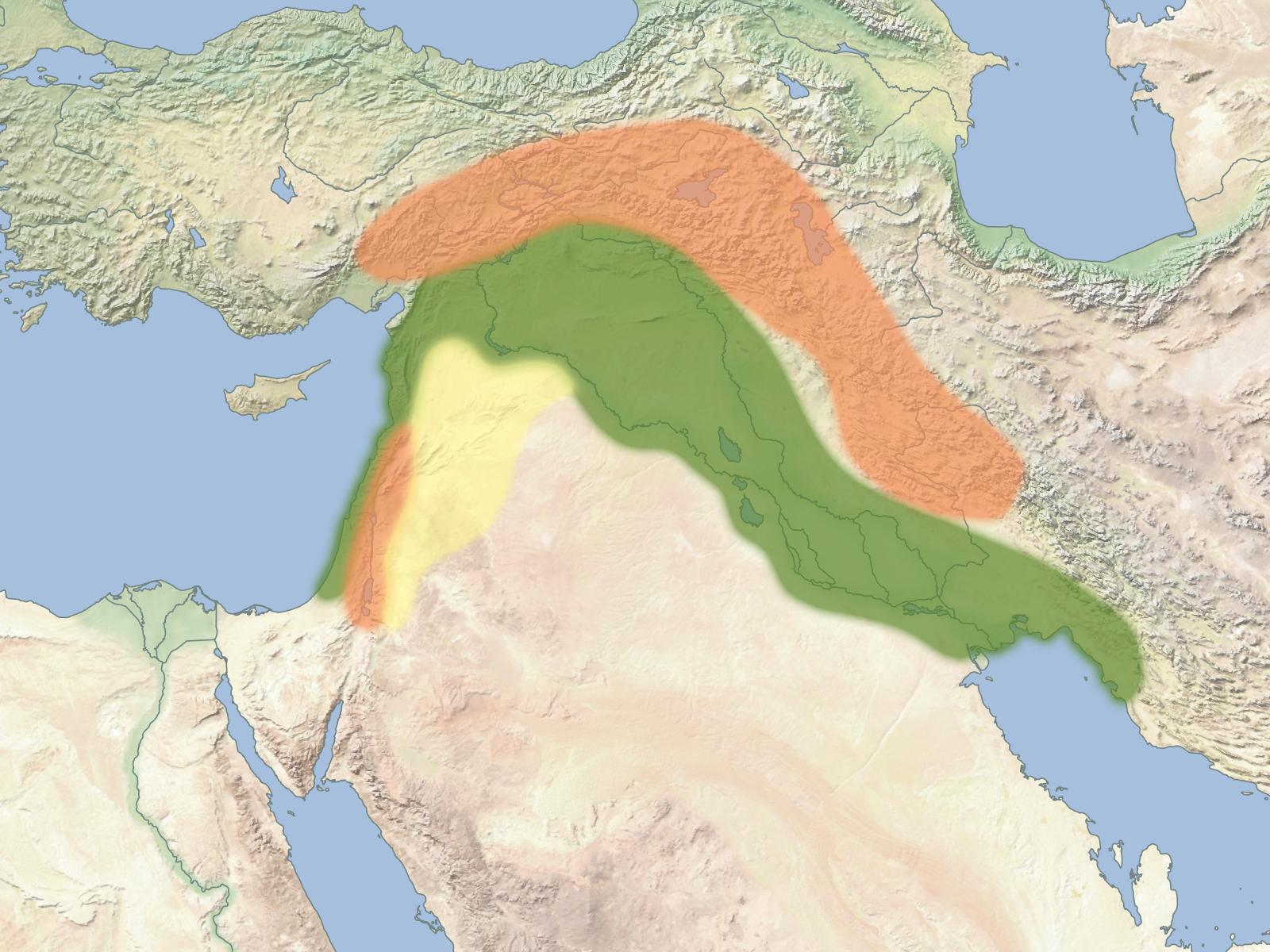

The “Fertile Crescent” is a not-very-precise term for the region where archaeologists have found the remains of the oldest urban societies; the “cradle of civilisation”. Something like the area shaded green on this map. It basically straddles two geographical zones: the Mediterranean coast of the Levant, and the floodplains of the Tigris and Euphrates (Mesopotamia). Some people also extend it to include the Nile/Egypt.

These two regions are “fertile” in the context of the generally arid Middle East: the Levant gets a steady stream of rain from the Mediterranean, enough to support rainfed agriculture; the Tigris-Euphrates used to flood annually in prehistory, depositing fertile sediment (like the Nile in Egypt), and could also be used for irrigation (as they are today).

But there are also two other “fertile” zones.

The orangey area on that map is what archaeologists call the “hilly flanks” – upland areas hugging the edge of the Fertile Crescent. In some ways they’re the true cradle of civilisation: they’re where the ancestors of the first city-dwellers domesticated the first crops (wheat, barley, lentils, etc.) and livestock (sheep, goat, cattle) and began to settle down in one place. Without that initial step, urban states wouldn’t have been possible, and again it happened in the Middle East before anywhere else in the world.

The yellow area is an “inner crescent”, where the fertile zone grades into desert. It’s an area of shrubland and grassland (steppe) which prehistoric people found ideal for grazing animals after they domesticated them, and which became the core region of the pastoral societies existing on the fringes of, and occasionally invading and toppling, the civilised urban states. The rest of the area inside the crescent is true, uninhabitable desert.

So the simple answer to your question becomes: the Fertile Crescent isn’t a desert. That or it always was. If we’re being strict about it, the “Fertile Crescent” is the bits of the Middle East that aren’t desert, and they still aren’t desert.

But clearly whatever definition you use there is quite a lot of desert in the equation. The Tigris and Euphrates are essentially a ribbon of green cutting through the Arabian desert. That precious rain from the Mediterranean dribbles to nothing a 100 km or so from the coast.+++(5)+++ These regions are like islands in a sea: the Tigris-Euphrates, the Mediterranean coast, the highlands, the steppe. They’re places people can make a living amongst an otherwise unhabitable.

So the environmental history of the Middle East is not a story of a fertile land becoming desert. Most of it is desert and it always has been. What has changed is how big those “islands” are: how far the Mediterranean rain gets, how big the floodplains are.

Climate change

The most obvious cause of these fluctuations is the climate, which has changed significantly over the past 25,000 years. In the Ice Age the whole region was much colder and wetter. The Mediterranean rains got much further inland and the Tigris-Euphrates flooded a much larger area. As a result the highlands were mostly wooded, and the nice lush coastal zone was much wider, as was the slightly drier steppe beyond that. The desert was restricted to the very dry interior of the Arabian peninsula.

Early agriculture in the region, which began towards the end of the Ice Age, therefore wasn’t particularly restricted to the Fertile Crescent. In fact, it seems that the some of the most productive areas where those on the periphery: the highland “hilly flanks” and the steppe. And people didn’t find marshy, flood-prone Mesopotamia very attractive at all.

Paradoxically, it seems that declining productivity is what brought about “civilisation”. Although people dabbled in agriculture for a long time beforehand, it wasn’t until the end of the Ice Age when they got serious about this settling down and growing things business, and it seems to have coincided with a short but acute arid period known as the Younger Dryas event.+++(5)+++

For a thousand years or so the islands of fertility shrunk dramatically, and the hotter, drier and generally climate forced people to fall back on foods they previously wouldn’t have bothered with—like weedy little cereals that take hours or grinding and baking before they’re edible—and invest more in ensuring they had a stable food supply by, for instance, attempting to capture and herd animals rather than simply hunting them.

After the Ice Age ended, the region became hotter and drier for good – but not straight away. The period between 10,000 and 7,000 years ago was actually the wettest time in the last 25,000 years. Having become quite attached to growing weedy little cereals and babysitting goats, people didn’t go back to the way it was before, though.+++(5)+++ They stuck with farming and found that the hard work paid off, with higher populations and food surpluses that allowed people to specialise in certain tasks and crafts, rather than having everyone spend all their time hunting and gathering. Again, in this period there wasn’t much of a Fertile Crescent – the islands of fertility were big and broad, and people still didn’t bother with Mesopotamia.

The period when people colonised the Tigris-Euphrates floodplains and began living in cities – became “civilised” in the classical sense – was again associated with a climatic downturn. The wet period at the end of the Ice Age was followed by another rapid and intense aridification event like the Younger Dryas (the 5.9 ka event). This seems to have pushed people to finally roll up their sleeves and start trying to make something out of the marshy black mud the two rivers dumped on their banks every year. And what they made was not just mudbrick houses, but complex irrigated agriculture, cities, monumental architecture, writing, and institutionalised social inequality.

This is the period when the “Fertile Crescent” comes into its own. The islands of fertility were shrinking, and as a result the Mediterranean coastal strip and, in particular, the land of the two rivers became places of extraordinary agricultural productivity and population density.

Unfortunately, they didn’t get a reprieve from the deteriorating climate after their eureka moment. The region has continued to get hotter and drier over the past six thousand years. As a result, the Mediterranean coastal zone and the floodplains have both shrunk dramatically, the steppe has all but disappeared, and the highlands have dried out and lost most of their woodlands.+++(5)+++ It’s all still there – there’s still a Fertile Crescent – but all significantly reduced in size.

Whether the steadily more arid climate, or later fluctuations similar to the Younger Dryas or the 5.9 ka event, affected the history of the societies that experienced them I won’t comment on. For one thing it’s going way out of my area as a prehistorian, and for another climatic/ecological explanations of social change are much less popular in the historical periods – as they should be, considering we’re dealing with much more complex societies with a much less straightforward relationship to their environment and ecology than in prehistory.

Human impact?

At this point you may be wondering why, god knows how many words in, I haven’t mentioned human induced desertification, considering u/Prufrock451 and u/The_Alaskan posted two great answers focused on it. That’s because I think that story is considerably murkier than is often presented (some of the below I’ve copied from my replies to them.)

People do, frequently and at length, discuss the Middle East as a “degraded”, “deteriorating” and/or “fragile” environment. Regrettably much of this goes back to the colonial period, when Europeans, who had trouble comprehending how the ancient ruins they were so keen on could have been built in the harsh, arid environment they were situated in, came up with the idea that it was a “man-made desert.” Of course, the idea that the historic Arab population had created a “ruined landscape” through their irresponsibility and mismanagement was convenient in justifying Europeans taking over the burden.

Of course, just because the idea has unsavoury colonialist roots, it doesn’t mean it isn’t plausible that the region has seen long-term, anthropogenic desertification. There are very detailed, scientifically-informed accounts of how, for example, irrigation could have led to a loss of soil fertility (as u/Prufrock451 described). The problem is that any human-driven changes took place against a backdrop of profound climate change over the past 25,000 years.+++(5)+++ When you’re looking at the archaeology and environmental proxy records it’s extremely difficult, if not impossible, to untangle the climate-induced and human-induced environmental change.

So while obviously farming, livestock grazing, deforestation, etc., by humans must have had a significant effect on the landscape, there’s a lot of debate about how resilient the wider environmental and ecological system is to these effects. The anthropogenic desertification hypothesis relies on some variant of a “tipping point” argument: that erosion and sloppy irrigation pushed the soil past its ability to recover its fertility, that deforestation and over-grazing damaged the ecology to the point it couldn’t regenerate lost forests and grassland.

But others would say that it’s simply impossible that prehistoric societies, using prehistoric technology, with prehistoric population densities, had such drastic effects on their environment. That once the soil was depleted and the pastures were gone people moved on, and the environment bounced back. And unfortunately, at the moment, we don’t have the hard environmental and archaeological evidence to say conclusively either way.

Is the Fertile Crescent fertile today?

All this raises the question, amongst the climate going this way and that, and humans maybe/maybe not destroying the environment, is the Fertile Crescent actually less “fertile” than it was historically?

The problem with framing the narrative in terms of lost “fertility” is that, by definition, fertility is culturally determined. You might be able to say objectively whether the physical environment is more or less arid, or whether the ecology is more or less productive, but if you’re asking if the region is less fertile or hospitable then you have to ask what it is people want from the landscape and how they’re going about getting it. When you take that into consideration, it’s not at all clear that the Fertile Crescent is less fertile. Or if it is, it’s arguably a lot more to do with cultural, demographic and technological change than it is environmental degradation.

The floodplain might have shrunk since the days of Sumer, but “Mesopotamia” supports a human population of 37 million people today. Iraq imports a lot of food, but still the Tigris and Euphrates must be producing an order of magnitude more food than it needed to support the comparatively tiny cities of antiquity.+++(5)+++

Environmental change might have chipped away at the area of the Fertile Crescent that can be farmed, advances in agricultural technology have multiplied how “fertile” that area is exponentially. Sure, it’s no longer the the the most agriculturally productive or most populous part of the world—not by a long shot—but in an era of aquifer irrigation, oil–based fertiliser and global competition, who’d expect it to be? Most of the world’s “breadbaskets” today were unfarmable steppe until modern farming technology unlocked their potential.

Summary

I suppose what I’m trying to say with the above, I’ve-thought-about-this-too-much wall of text is three things:

-

The Fertile Crescent has not become un-fertile. In many ways, it is more “fertile” now than it has even been, although that’s a very difficult thing to measure when you unpick it. It is by no means the most agriculturally productive place in the world, but the idea that it ever was is really just a product of it being particularly well suited for a particular kind of agriculture in a particular time and place that, as it turns out, was particularly significant for world history.

-

The Middle East has become progressively drier and hotter since the height of the last Ice Age twenty thousand years ago. In step, the more hospitable “island” zones (including the Fertile Crescent) have retracted and the desert has expanded. The obvious conclusion is that the former is the primary driver of the latter.

-

Having said that, we can’t discount the possibility that humans have accelerated, or in places even caused, the desertification process. But at the moment there just isn’t enough evidence to say conclusively, and we should be wary of colonialist fairy tales of landscapes ruined by irresponsible Arabs.