Source: here.

Some further notes on the Mongol religion-3

The core of the material discussed in this note is based on the publications of the Hungarian-Mongolian Joint Expedition studying folk traditions in Mongolia and the masterly work of Igor de Rachewiltz on religion in the Secret History of the Mongols (SHM). We take a look at this material from a comparative religions and historical perspective. A primer.

In the Ṛgveda, the deities Dyaus and Pṛthivī (alternatively known as Bhūmī or Kṣāmā) generally occur as dyad — a devatā-dvandva of the form Dyāvāpṛthivī or Dyāvābhūmī or Dyāvākṣāmā — that may be rendered as Heaven and Earth. These devatā-dvandva-s are mentioned a total of 122 times in the RV. They are understood both as the parents of the gods and the universe (e.g., ya ime dyāvāpṛthivī janitrī rūpair apiṃśad bhuvanāni viśvā ।), and the stage for their acts. Imagine a religious system where these other gods recede into that backdrop or reside in a hidden realm that can only be seen by special individuals. What we would end up with is something like the overt religious system of the SHM. In that primal history (epic) of the Chingizid Mongols the chief religious protagonists are a precise cognate of the Indo-Aryan devatā-dvandva Dyāvāpṛthivī. In the Mongolian, it occurs in the form Tenggeri[Tengri]-Qajar, with Tengri being the cognate of Dyaus and Qajar being the cognate of Pṛthivī. Together, Tengri-Qajar are said to shape human events (Mo: jayaghan ~ destiny), provide the foundation for the existence of animals, and give “increase”, power, strength and protection. As per the SHM, together they conferred on Temüjin the lordship of the ulus and, in the same text, they are elsewhere mentioned as protecting Chingiz Khan and his army. They are explicitly mentioned to have aided Temüjin in the campaign again the Merkits along with Toghrul Wang Khan and Jamuqa to recover his wife, Börte. Thus, generally, the role of the Mongolian devatā-dvandva matches quite well with the Indo-Aryan Dyāvāpṛthivī. For instance, Atri invokes the dyad thusly:

ā suṣṭutī namasā vartayadhyai

dyāvā vājāya pṛthivī amṛdhre ।

pitā mātā madhuvacāḥ suhastā

bhare-bhare no yaśasāv aviṣṭām ॥ (RV 5.43.2)

With good praise, with obeisance, they are turned to,

Heaven and Earth, for not disregarding [our] quest for booty.

Father and Mother, of mellifluous speech and good hands,

In battle after battle, the famed dyad protects us.

The Mongolian Tengri is described as a mighty being (erketü) and has an element of the Father-figure seen in IE tradition — this is expressed in the tale of Alan Qo’a’s heaven-born sons (Tengri-yin kö’üt). Notably, the divine imagery of the Chingizid Mongols, overlaps with that seen in the Gök-Turk inscriptions on the Orkhon steles. The Gök-Turks too had the dyad of the Heaven deity (Tengri) and the Earth deity (Yer). As per the records of the Tang, the Turkic Khaghans performed a sacrifice to Tengri at a specific spot rendered as “大人” (da-jen), likely corresponding to Turkic Tazin, in the second decad of the 5th month annually. This spot was identified by de Rachewiltz as being along the Tesiin Gol river, probably Tes in Northwestern Mongolia (Figure 1).

Interestingly, the Mongols had a second word for their Earth deity, especially when used in a concrete form — Ötögen or Etügen. Under this name, her concrete aspects, like the holder of the mountains and rivers, as in the case of her IA counterpart, are mentioned. This Mongolian word appears to be a possible loan from the Turkic word Ötüken, which appears to refer to the sacred mountain where the Turkic Khaghans offered their sacrifices to the Earth goddess. As with Tazin, the exact locale of Ötüken remains uncertain, but it was likely a spot in the Khangai range, to the West of the old Turkic capital at or in the vicinity of Ordu Baliq of the Uighur Khaghans (Figure 1). This suggests that an element of the religion of the Chingizid Mongols shared a continuity with that of the Gök-Turks and Uighurs who ruled Mongolia before them and the Khitans. Despite Heaven and Earth being quintessentially universal deities, in the Turkic case, they had specific cultic locales in Mongolia. It is not clear if this was the case with the Mongols. We do know that the Chingizid capital Qara Qorum is close to the old Uighur Ordu Baliq and the Gök-Turk capital suggesting a certain continuity at least for the Khaghanal seat. Further, there is an extensive folk mythology connecting the topos of Mongolia to near mythical acts of Chingiz Khan and his family. From the SHM we learn that the Mongols performed a sacrifice with burnt offerings known as the Qajaru-Inerü evidently to the Earth-deity as the protectoress of the ancestors. While this is reminiscent of the Turkic ritual at Ötüken, there are no indications that it was performed in a specific place in Mongolia. However, the SHM does mention a ritual performed by Chingiz Khan at Burqan Qaldun in the eastern reaches of North-Central Mongolia. It was done in the morning, facing the sun and bowing 9 times, wearing the belt around the neck (c.f. yajñopavīta) with the headdress taken off. It seems to have been accompanied by a prayer incantation. The importance of Burqan Qaldun to this date suggests that Mongols too had specific locales for their worship.

More generally, there are several references to the Mongol worship of Tengri and probably Qajar on mountains. The worship of Tengri seems to have been performed before major campaigns by Chingiz Khan, his generals and successors. Rashid al-din mentions Chingiz Khan’s rite on a mountaintop before the 1211 CE campaign against the Jurchen. Here, he is said to have specifically asked Tengri to help him avenge the deaths of Ambaqai Khan and Ökin Barqaq, former leaders of the Mongols who had been brutally executed by the Jurchen. It is not clear if he just chose some accessible hilltop or whether it was a special locale or it was done at Burqan Qaldun. He did similarly before heading to punish the Khwarazm Shah. The worship of Tengri also comes in the context of another war. For some background: starting in 1207 CE Chingiz Khan and his son Jochi moved to subdue the taiga chiefdoms, beginning with the Kirghiz. This was followed in 1208 CE with the conquest of the Oirat, and their leader Quduqa-beki joined the Mongols as a general of Jochi. He then aided in the subjugation of the Buriyat, Ursut, Qabqanas and others. This was completed by the autumn of that year and towards its end Quduqa-beki acted as a guide for Jochi’s forces to locate the holdouts of the Merkits and the Naimans in the Northwest. They were smashed in the battled of the Irtysh River that followed. Probably, in 1209 CE another taiga tribe, the Qori-Tumat, were conquered on the West bank of the Baikal. In 1217 CE, the Qori-Tumat started a rebellion against the Mongols. Chingiz Khan sent his senior general Boroqul to suppress it, but he was ambushed and killed. To add to this, the Kirghiz refused to aid the Mongols in the campaign against the Qori-Tumat, and several other taiga chiefdoms joined in their revolt. Thus, in 1218-19 CE, Chingiz Khan sent his son Jochi to crush the Kirghiz and subjugate tribes such as the Telenguts and Keshdim, and his general Dörbei Doqshin to put down the Qori-Tumat. Evidently, expecting this to be a difficult campaign, the Khan asked Dörbei to worship Tengri after arraying his army in strict order before setting out against the Qori-Tumat. In a similar vein, the grandson of Chingiz Khan, Batu, performed the hilltop worship of Tengri before the battle of Mohi with the Hungarians (mentioned by Ala al-din Ata-malik Juvaini in his history of the Mongols).

What about the rest of the Mongol religion? While we get tantalizing hints, like the ritual performed by the Kereit for the birth of a son but no further details. However, the biggest element that is repeatedly mentioned but never described in terms of the actual ritual content or incantations is the role of the shamans. This suggests that the authors of the SHM, while embedded in the shamanic religious system, were unlikely to have themselves been performers. One wonders if this might relate to the efforts of the notorious Kököcü Teb Tenggeri, Chingiz Khan’s first shaman, to seize political power. Nevertheless, the shamans of the descendants of Qasar and their tribe, the Qorcin Mongols, to date, claim their shamans to have descended from this Kököcü. The name of the Chingiz Khan’s shaman indicates a connection to Tengri though its exact significance remains unclear. Hence, to uncover this “unspoken” layer of the religious tradition, one has to turn to modern studies on Mongolian shamanism. Across the extant Mongol horizon, we see that the modern shamans use peculiar effigies or icons known as ongod (singular ongon; Figure 2). These icons might represent tengernüd, i.e., tengri-s (gods), jayāchnūd, (semi-)divine beings controlling destiny, and human ancestors. The shamans also invoke other Tengri-s and deified shamans who might or might not be represented iconically (e.g., Khan Jayaghachi Tengri or Dayan Deerkh). The icons are made of felt (as they were in early Mongol history) or other materials like metals. It is in this context the testimony of the Venetian traveler Marco Polo becomes relevant (despite de Rachewiltz doubting the veracity of his account). While his account is confused, he specifically mentions that Mongols place images of their deities (referring to Tengri-Qajar and apparently also other tengri-s who are their children) made of felt or other fabric in a place of great honor in their tents. He mentions them making food offerings to these icons and worshiping them for protection. This is clearly a reference to the ongod, also noticed by other Western emissaries to the Empire. Comparable worship of ongod continues to the current time among the Qasarids and the Mongolized Tuvinian Turks. Further, keeping with the children of the Tengri-Qajar parent pair noted by Marco Polo, among the Buriyats the children of the Heaven Tengri are invoked in shamanic rites and called noyad (singular noyan ~ chief). For example, Poppe records this chant in the luck-beckoning dalalgha ritual (as provided by Krystyna Chabros in her monograph on these rituals):

“These are the inviolable benefits (buyan) of your Tengri and noyad and ugh qarbul (=origins: ancestors of the clan), the good fortune wishing-jewel which cannot be called, the great dalalgha of becoming rich and prolific.”

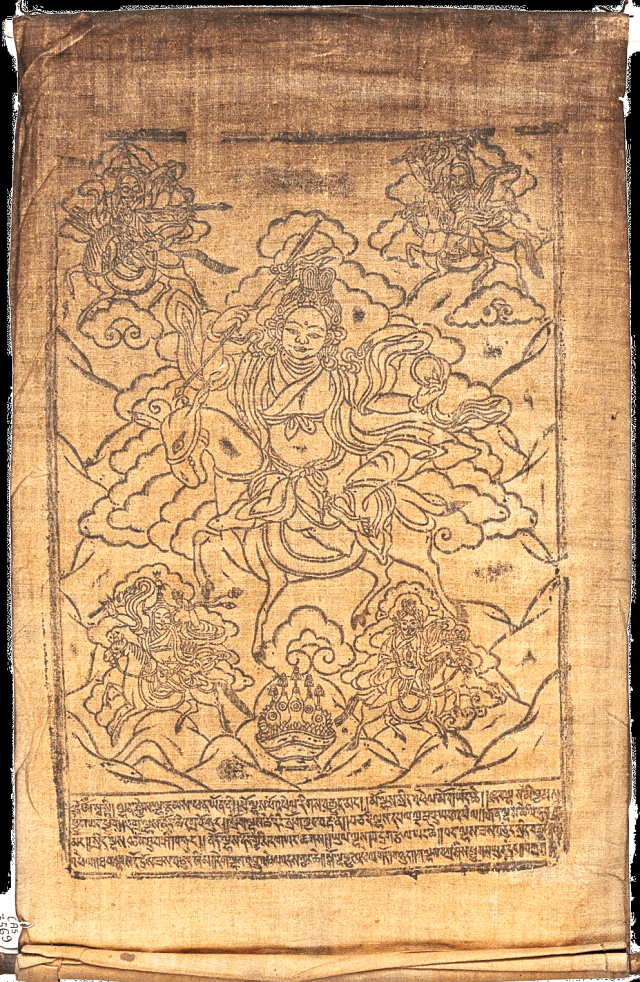

Figure 2. Ongod of the Qorchin shamans recorded by Veronika Zikmundová

Though the SHM might not record the contents or liturgies of shamanic rites, the extant shamanic tradition preserves a memory of the connection of Chingiz Khan’s family with such. One is a peculiar mythological epic regarding one of Chingiz Khan’s daughters. Apart from his four sons, he had 5 daughters, Qojin, Checheyigen, Alaqa, Tümelün and Al Altan; however, it is not clear which of these daughters the tale refers to. The outline of the tale as per surviving records involves the Khan’s daughter being attacked by a shape-shifting demon. In a motif resembling that in the Rāmāyaṇa, the demon appeared before the girl as a monk seeking alms. Then revealing his true form, he tries to seize her in a chase that spans the triple world. The Khan’s daughter finally defeats him after being helped in each stage of the chase by her horse, zoomorphic spirit guides emanated by the horse, viz., a red fox, a blue fox and a cat, crow messengers (recapitulating the Germanic Odinic motif), and the famed dogs of Turko-Mongol mythology, Qasar and Basar. This constellation of motifs is clearly a recapitulation of the famed shamanic trance journey aided by zoomorphic psychopomps. Though an extant Mongol folk epic, this tale seems to capture key elements of the original Mongolic shamanism. Similarly, Chingiz Khan’s third son, Chaghadai and his wife Changqulang, who are invoked by the Buriyats in their fire-kindling rituals (just as other Chingizids are invoked in various fire-kindling rites), also exist posthumously as key psychopomps of their shamans.

The rituals of shamanesses recorded by Agnes Birtalan among the Darkhads of Khövsgöl also appear to preserve archaic elements that give clues regarding shamanic practice in the classical age. Sometime in the late 1600s, a group of iron-working Turks related to the Tuvinians and with connections going back to the Uighurs of yore were the subjects of the Mongol lord Geleg Noyan. He in turn offered himself as a subject to the famous mantravādin Jñānavajra (Öndör Gegeen). The Darkhads thus received some privileges and adopted the Mongolian language. Despite their association with the Vajrayāna savant, many Darkhad shamans remained in opposition to the tāthāgata-mata and retained their old shamanism. Their shamanic practice, involves ongod reminiscent of those seen by Marco Polo. Among others, their shamanesses channel ghosts of various humans as well as zoomorphic psychopomps who indicate their presence by emitting various animal calls through the shamanesses. One interesting case records a shamaness ritually channeling the ghost of a Turk (ancestor?) who started speaking in the Tuvinian Uighur language. When they told him they could not understand, he switched from Turkic to Mongolian that they could. Apparently, the shamaness did not know the Turkic dialect in regular life but could only speak it in a deep trance (xenoglossy). Additionally, in day time rituals the shaman(ess) produces music with a morsing (kamus) and uses a mirror (reminiscent of old Saka ritualists worshiping their Solar goddess). It is notable that when the shamaness invoked some of her psychopomps, she called on them to worship a group of 5 Tengri-s known as the Jayaghachi tabun tengger of the ongon. The exact origin of these 5 deities is unclear (Figure 3). Even though they might be depicted in iconographies inherited from Tibet (i.e., Vajrayāna imagery), there is no evidence for them having any connection to the Vajrayāna. Also remarkable is the invocation of the psychopomps from specific rivers and mountains, usually the locations where the ancestors of the shamans lived. This suggests that like the specific topos of the state cult of the Gök Turks, the shamans of the Chingizid Mongols too might have invoked their psychopomps in connection to specific places.

Finally, we hold that the extant shamanic liturgy does preserve certain archaisms concerning the worship of the Heaven Tengri and Qajar of the old Mongols (i.e., as in the SHM) despite the later Bauddha influences. For example, in the rite of the nine-yak tail standard of the Khan performed by the Qorchin Mongols invoking Sulde Tengri, we also see an invocation of the missiles of the Heaven Tengri (recorded by Chabros). Here, peculiar objects found on the steppe, like meteorites and sometimes ancient bronzes of the pre-Turko-Mongol age, termed “tngri-yin sum u” (missiles of Tengri) are used in the ritual with the usual Mongol qurui call. Further, among the shamanic invocations of deities of ultimately Hindu origin like Kubera Vaiśravaṇa and the river Gaṅgā (identified with the ocean = dalai by the Mongols), we find formulae relating to the Heaven-Earth dyad of the SHM. For instance, Walther Heissig records:

The benefits of Möngke Tengri the father, qurui qurui.

The benefits of the earth of the seventy-seven-layered Etiigen, the mother, qurui qurui.

The benefits of the son bright as the sun, moon and stars qurui qurui (Evidently the son of the divine pair, like the noyad in above incantation).

The benefits of the constellation of the seven old men (Ursa Major) and the other teeming ten-million stars qurui qurui.

We also have a shamanic incantation found widely among different extant Mongol groups that is directly related to the role Tengri has in the SHM as the provider of sustenance to the animals (below is the translation of the Bulgan version recorded by Chabros):

In the dark night

My Khan, powerful Tengri showing mercy

May my black horse-herds spend the night in peace and good health.

The last two elements of the term Khan erketü Tengri found in the above incantation occur in the SHM as is (c.f. ed-un Khaghan Bisman Tengri for Kubera — the emperor of wealth — a construction ultimately traceable to the Taittirīya-śruti).

Similarly, we have the below chant used in the animal sacrifice by the butcher rather than the shaman (recorded by Chabros):

OṂ may happiness prevail.

Eternal Möngke Tengri

Blooming golden Earth

My blue Mongol homeland

lying on your southern slopes

pasturing in your sheltered places

deign to grant the benefits of bulls with fine humps,

the benefits of cows with fine udders.

qurui qurui qurui

The benefit of Chingiz, the Khaghan

foremost among all the animals

may they come returning

to their owner who cared for them.

qurui qurui qurui.

It is notable that this otherwise archaic chant with a clear memory of Chingiz Khan incorporates an initial OṂ from the Indic tradition.

Lastly, we have the remarkable incense offering to Tengri and Etügen preserved among the Oirats and their Bayad cousins recorded by Heissig and Chabros which calls on Möngke Tengri to make joyful Etügen, and the genii of locii and the waters.