Source: here.

Journey to the East

Journey to the East

Investigating the possible origins of a Brāhmaṇa Kehan in the Rouran Khaganate

Mar 31

8

2

Share this post

Journey to the East

We would first like to thank Professor Emeritus Peter B > Golden who was kind > enough to give his authoritative words on our burner emails which > enabled us to write this essay. > Also a lot of thanks to > @ShreshtVenkat on Twitter for > helping us with translations and being an outlet for discussions.

Introduction

The Mongols have been a subject of our fascination for a long time. Recently while studying the Mongol Yuan Empire we learned of many cultural exchanges between Hindus from India and China. This naturally prompted us to go further in the past and learned of the same during the Tang Dynasty. While these two Eras have been the subject of much academic fascination, the time preceding them has not received the discussion they merit. With few English medium journals available online to study the matter — we began to scrape Chinese primary sources of history ourselves. While in any other age, it would have been impossible for us to understand these treatises, modern technologies likeDeepLdelivered us fairly sensible translations which were helpful.

Unlike India, China has had a very rich courtly culture of writing Imperial Histories. So we began with the Imperial History of Sui [581-618], the dynasty preceding the Tang. From this, we learned about many “Brahmana” treatises relating to Astronomy, Medicine and Mathematics, which were fairly popular in this period. It should be noted that Nasitka works which were written by men of Brahmana descent do not receive such treatment in titles instead they’re explicitly called Nastika. We also learn of treatises on the geography of China that likewise travelled west to India.

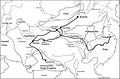

Largely from SeiShu Volume 34. Translations by DeepL

We were greatly pleased by collecting such bits of information alone and started to scrape through other Imperial Histories like those of the Northern Wei, which had preceded the Sui. It was while translating the ninety-eighth volume of the History of the Northern Dynasties that we came across some rather overwhelming information:

阿那瑰來奔之後,其從父兄俟力發婆羅門率數萬人入討示發,破之。 > 示發走奔地豆幹,為其所殺。推婆羅門為主,號彌偶可社句可汗,魏言安靜也。時安北將軍、懷朔鎮將楊鈞表:「傳聞彼人已立主,是阿那瑰同堂兄弟。夷人獸心,已相君長,恐未肯以殺兄之人,郊迎其弟。輕往虛反,徒損國威。自非廣加兵眾,無以送其入北。」二月,明帝詔舊經蠕蠕,使者牒雲具仁往,喻婆羅門迎阿那瑰復籓之意。婆羅門殊自驕慢,無遜避之心,責具仁禮敬,具仁執節不屈。婆羅門遣大官莫何去汾、俟斤丘升頭六人,將兵二千隨具仁迎阿那瑰。五月,具仁還鎮,論彼事勢。阿那瑰慮不敢入,表求還京。 >

Approximate Translation from DeepL: [We’ll give the correct account > later] > After the arrival of Anangui, his father’s elder brother’s son, > Brahmin, led tens of thousands of people to attack Qilifa Shefa and > destroyed him. > *Shefa ran away to Didougan and was killed by him. Brahman was elected > to be the lord, and was titled Mioukesheju Kehan, the Wei word for > peace and quiet. At that time, the general of Anbei, General Yang Jun > of Huaishuo town, said:

“I heard that they have established a master, > who is the same cousin of Anagui. The barbarians have the heart of a > beast, I’m afraid he will not welcome his brother but kill him. If > they go to the enemy lightly, they will only damage the prestige of > the Chinese nation. The government will not be able to send them to > the north unless they increase their troops widely.”*

In the second month of February, the emperor sent an imperial edict > to the Rouran. Brahmin was so proud of himself that he had no desire > to withdraw, but he rebuked Gouren for refusing to yield courtesy. > Brahmin sent six officials, Mo He Fen and Qi Jin Qiu Sheng Tou, and > 2,000 soldiers to accompany Gou Ren to welcome Anangui. In May, Gouren > returned to the town and discussed the situation. Anagui was afraid to > enter, and asked to return to the capital.

I’ve not translated the entire episode here but as it becomes apparent, there was one YuJiuLu PoLuoMen [郁久閭婆羅門] that is translated as Brahman [婆羅門: PoLuoMen] here. This man from the Rouran Khaganate was a cousin of Anagui and became Khan at one point when Qilifa Shefa launched a Coup d’etat against Anagui and forced him to flee. At this point, PoLuoMen was elected the Lord of the Khaganate and titled Mioukesheju Kehan, meaning peaceful Khan. It should be noted that PoLuoMen is exclusively used for defining Brahmana-s across Chinese Imperial Histories. Thus, it would seem that said Khan was a Brahmana himself. However, a claim of such substance must be critically examined before being asserted at all. One should naturally recoil and ask how this is possible. Is the translation correct? Is the transcription correct? Perhaps it is an approximation of some other name? Isn’t he just another member of the YuJiuLu family? Even if a Brahmana, what was he doing there? How can a foreigner from so far away become a member of the ruling family? Even if he becomes one how can launch a coup and seize power? In this essay, we shall do the same and attempt to theorize his seemingly unwarranted presence in the Chinggizid Steppes by going through various episodes of Chinese history related to Brahmanas and also revealing the internal mechanism of Steppe-Han societies and their interaction.

Examination

WERE BRAHMANAS PRESENT AS A DISTINCT GROUP IN CHINA?

The presence of Indians, Nastikas in particular in China and Central Asia is uncontested and well documented. Just previously we noted that there were a lot of Brahman treatises documented during the Sui Reign. Generally, we find such transmission through Nastika Brahmanas whose ethnic identity is not stressed upon. The prominence of Brahmana treatises as opposed to Nastika treatises had not popped up in a vacuum. The times preceding the Sui had overseen two great persecutions of Nastikas. The one directly before the Sui was carried out by the Northern Zhou Emperor Wu [543-578]. In the year 574, the Emperor brought forth Confucianist, Daoist and Nastika scholars for a debate and decided that the Daoists and Nastikas were useless and banned them. All the monks were ordered to return to the lives of commoners and their privileges were retracted. Much before that during the reign of the Northern Wei Emperor Taiwu [408– 452], we hear of an interesting episode from the Book of Wei, Volume 130:

及得寇謙之道,帝以清淨無為,有仙化之證,遂信行其術。時司徒崔浩,博學多聞,帝每訪以大事。浩奉謙之道,尤不信佛,與帝言,數加非毀,常謂虛誕,為世費害。帝以其辯博,頗信之。會蓋吳反杏城,關中騷動,帝乃西伐,至於長安。先是,長安沙門種麥寺內,御騶牧馬於麥中,帝入觀馬。沙門飲從官酒,從官入其便室,見大有弓矢矛盾,出以奏聞。帝怒曰:「此非沙門所用,當與蓋吳通謀,規害人耳! > 命有司案誅一寺,閱其財產,大得釀酒具及州郡牧守富人所寄藏物,蓋以萬計。又為屈室,與貴室女私行淫亂。帝既忿沙門非法,浩時從行,因進其說。詔誅長安沙門,焚破佛像,敕留臺下四方令,一依長安行事。又詔曰:「彼沙門者,假西戎虛誕,妄生妖孽,非所以一齊政化,布淳德於天下也。自王公已下,有私養沙門者,皆送官曹,不得隱匿。限今年二月十五日,過期不出,沙門身死,容止者誅一門。」 >

Approx Translation: >

The Emperor was a follower of Kou Qianzhi [Daoist Monk] and followed > the policy of Wu-Wei [Inaction]. At that time, the Emperor used to > discuss issues with Cui Hao, the Secretary, who was very > knowledgeable. Cui Hao followed the way of Qian and especially didn’t > believe in the Nastika doctrine. He filled the Emperor’s ears with > thoughts hateful of the Nastikas. The Emperor was convinced by his > knowledgeable arguments as he was a good speaker.

One day in Chang’an, > the Nastika monks planted wheat in the temple, and the Emperor entered > the temple to watch the horses being grazed by the imperial swordsmen. > When the monk was drinking with the officials, the officials entered > his chamber and saw a large amount of bows and arrows, and reported it > to the Emperor. The Emperor said:

“This is not to be used by the > monks, they must have conspired with Gai Wu [Xiongnu Rebel], > planning to harm people’s heads!” >

He ordered the officials to investigate and punish a temple and > examine its property, and found a large amount of wine making > equipment and other tens of thousands of hidden things the wealthy > people of the state and county had sent. The chamber of law there also > served as a house for nobles to have illicit sex with girls. The > Emperor was angry with the monks for being unlawful and disregarding > his advice, therefore he passed an edict.

The imperial edict ordered > the death of all Nastikamonks in Chang’an, burned the statues of the > Sakyasimha, and made orders to confine monks within the four quarters > of their monasteries. The imperial edict also said:

“The nastika monks > faked births of “Xirong” and gave shelter to evil doers, they don’t > unify the government or spread virtue in the world. Since the princes > are involved, they will send all their private monks to the official > Cao and must not hide. The deadline is the 15th of February this year, > after the deadline, those who have not returned from the nastika ways > will die and those who protect them will be punished as well.”

We learn that in 446, Emperor Taiwu punished all the Nastikas by death for aiding rebels and being corrupt. This raises the question of to what degree were Brahmana and Nastika Brahmanas differentiated in Chinese courts. To answer this, we shall look at Sima Guang’s Zhizhi Tongji here:

穹翘“彼公时旧臣虽老,犹有智策,知今已杀尽,岂非天资我邪!取彼亦不须我兵刃,此有善咒婆罗门,当使鬼缚以来耳。 >

“Although his old ministers are old, they still have wisdom and > strategy, and they know that they have been killed today, is it not a > gift from heaven? Take him, you do not need my blade, here is a > brahman who is good at spells, he can make the ghosts bound to the > ear.”

Concerning the fate of the ministers of his enemy, Emperor Taiwu tells his aide that he doesn’t need his blade to kill them. Instead, he should take a Brahmana who was skilled in incantations and could bind ghosts to the ear. This event transpires in 450 AD, just four years after his edict punishing Nastikas by death. Thus, this indicates that the Chinese and the Xianbei Tuobas saw a difference between the Nastika Brahmanas and Vaidika Brahmanas. In the preceding centuries, Daoism too had many developments which some scholars believe came from Brahmana influence. There is also the tale of a Sri Lankan Brahmana recorded by Shi Huijiao [慧皎, 497-554] in his Gaoseng Zhuan [高僧傳]:

Soon afterwards, a Brahmin in Sri Lanka, patriarch of their religion, > was eloquent and knowledgeable. Having read nine in ten of the books > in the west and being able to recite most of them, he heard of > Kumārajīva’s efforts to propagate Nastikamta in Guanzhong, and then > told his disciples:

“How can we sit here and see Sakyasimha’s > Teachings spreading in China without promoting our Arya religion?”

Thereupon, he came to Chang’an by riding on a camel and carried his books with him. Yao Xing was amazed by his strange appearance. The Brahmin reported to the ruler:

“The ultimate Truth has no fixed form; > it depends on the facts. Now I want to challenge the bhiksus in > Guanzhong by having a debate; the winner should transmit his > doctrines.”

Yao Xing approved.

The Brahmana ultimately loses the debate on account of his ignorance of Chinese Classics. However, this does tell us that they were active in proselytization and different from their Nastika counterparts. As usual, he was unnamed and only called PoLuoMen [婆羅門]. From various sources, we also learn of Nastika monks who were born originally into Brahmana families, however, they are not referred to by that ethnonym later. Gunabhadra and Buddhayashas would be two such examples from our Gaoseng Zhuan.

Mural of the R̥ṣi Vasiṣṭha from the Mogao caves

HOW POLITICALLY POWERFUL COULD INDIANS GET IN THE SINOSPHERE?

Under the Confucianist doctrine of Tianxia [all under heaven], the Chinese considered themselves the most advanced and civilized state and the rest barbarians. India, however, held a different place as the Shufan [Civilized Barbarian] in Confucianist doctrines as opposed to other non-Han barbarians.+++(4)+++ To Chinese Nastikas, India’s position was even more special as seen in the works of the Tang Era monk Daoxuan. Daoxuan made cultural comparisons and argued that India was the centre of the world, not China. He gives us calculations based on distances between mountains and seas to assert the same. He praises the sophistication of Indian literature and culture which the Chinese seemed to lack. He criticizes the Chinese script and language for having no legitimate origins and lacking alphabets. The Indian language and script were created by Brahmā himself. But were these appraisals, undue or otherwise, just limited to clerical debates or did they have implications on the status of Indians who lived in China as well?

To answer that we shall first examine the responses of Indians against the Tang Emperor Xuanzong’s edict of 740. The imperial edict explicitly orders all foreign monks to immediately leave China. The reasons had been accumulating but the final cause of this edict was much like Emperor Taiwu’s far harsher edict. A Nastika monk Bao Hua had conspired with rebels to overthrow Tang Dynasty just like the Nastikas in Northern Wei conspired with the Xiongnu rebels.+++(4)+++ While foreigners were indeed forced to leave — Indian monks were indifferent to the imperial edict. This is witnessed in Vajrabodhi’s bold reply to the edict:

I am a monk from India [fanseng], not some foreign barbarian > [fanhu: Central Asian/ Tibetan Nastika]. The imperial edict has no > relevance for me. There is no way that I will leave China.

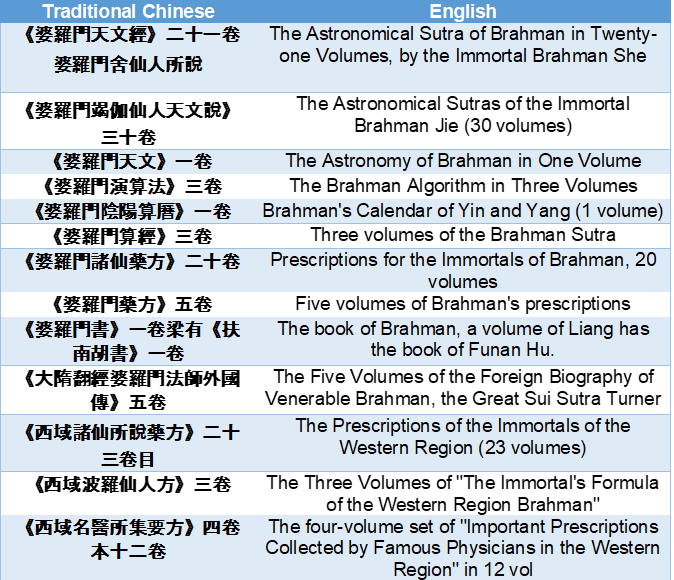

Even seemingly defying imperial decree is a bold step that one cannot risk unless they’re truly secure about political relevance. Speaking of which, it was the risk of the growing political relevance of Nastika monks which compelled the Emperor to pass this edict. He was afraid that his wife, Empress Wang, would tread in the footsteps of the previous Empress Wu Zhetian [665-705] who had usurped all power and was the de facto ruler of China for four decades. She had tactfully made use of Nastikamata and employed Indians in offices to legitimise herself as a Chakravartin.+++(4)+++ We learn of multiple families of Brahmana astronomers that staffed the Tang Bureau of Astronomy during her reign. The most famous one was Rahula, who was the director of the bureau for more than three decades and interpreted heavenly signs on behalf of the Empress. His installation too was a part of her legitimization program. A manuscript describing the thirty people working under her lover, the nastika monk Huaiyin reveals that nine of them were Indian nationals with many Brahmanas.

Another episode from the Tang Era informs us about the political prominence of such skilled foreigners. The Chinese are infamous for losing their monarchs to immortality drugs, something Emperor Taizong criticized as a foolish pursuit in his early days. By 648 however, he has a change of heart due to his sickness and is pleased to learn when his envoy Wang Xuance brings back a Brahmana Nārāyaṇasvāmi who was capable of concocting immortality drugs.+++(4)+++ Previously we noted the great circulation of Brahmana treatises on medicine carrying the word “immortal” on them as well. There was a long-standing belief that Brahmana medicine could increase one’s lifespan. Brahmana medicine was circulated in popular culture as well. The Tang Era Poet Liu Yuxi was suffering from an eye disease, possibly a cataract, and was cured by a Brahmana with golden instruments. Later he wrote a famous describing it:

三秋傷望遠,終日泣途窮。

兩目今先暗,中年似老翁。

看朱漸成碧,羞日不禁風。

師有金蓖術,如何為發朦 >Rough translation: >

In the third autumn, I was sad to see far away, and I cried for the whole day that the way was poor.

My eyes are now dark, and I look like an old man in my middle age.

Seeing that the vermilion is becoming blue, I am ashamed of the sun, but I cannot help the wind.

The teacher has a golden castor technique, how can he make it hazy

So, when Nārāyaṇasvāmi is brought to Taizong’s court, he is given a warm welcome and immediately put in charge of the Office of Precious Metals. The Emperor also assigns his Minister of War, Cui Dunli to Nārāyaṇasvāmi’s service so that all his needs are looked after. Envoys are sent in all four directions to fetch rare herbs and stones for the same.

As expected, the immortality drug doesn’t work and the Emperor dies soon after. Later, when Taizong’s son Gaozong takes over as the Emperor the court wishes to charge Nārāyaṇasvāmi with Taizong’s murder by administering false immortality drugs. However, they are unable to do so and instead have to punish Wang Xuance for bringing him to court. Wang Xuance attempts his best to defend Nārāyaṇasvāmi’s abilities but fails. Wang Xuance is ultimately charged with trickery and lying by Emperor Gaozong and the powerful minister Li Ji. Whereas Nārāyaṇasvāmi is merely asked to leave back for India. Now, one may wonder why could Nārāyaṇasvāmi not be punished, and the answer lies in a memorial presented by the high official He Chujun, the memorial to Gaozong reads:

Lifespan is based on destiny. It cannot be extended through drugs.

During the final years of the Zhenguan era, the previous Emperor Taizong had taken drugs concocted by Nārāyaṇasvāmi , but without any > success. At the time of Great Demise of Taizong, the whereabouts of the famous doctor were unknown.

Thus the critics turned to blame > Nārāyaṇasvāmi. They wanted to expose him and have him put to death.

However, fearing that the barbarians would be agitated over the > matter, they restrained themselves. The previous example of the > incompetency of life-prolonging physicians is not in the distant past. > We hope His Majesty will examine the matter carefully.

The court had indeed wished to punish Nārāyaṇasvāmi, but they feared that the barbarians would be agitated if something happens to him and thus choose Wang Xuance as their fall guy. These barbarians in all likelihood refer to Indians here, we have established the significant presence of Brahmanas and Nastikas already. This paragraph is particularly interesting as it reflects the power of the Indian diaspora.+++(4)+++ A man who is suspected of having killed the Emperor couldn’t be punished over the fear of possible agitations in return. It is possible that it had something to do with maintaining good relations with emerging powers in India who may take offence. However, it should not be too surprising since we are aware of Brahmanas borns in military positions as well apart from the spiritual and intellectual ones. The famous Nastika monk Amoghavajra is described to be the son of a Brahmana living in Samarkand. In 750, he was invited by Geshu Han to aid his governorship and is said to have stopped the advance of a 200,000-strong Uyghur and Tibetan army by performing Nastika rituals.

INTERMARRIAGE AND ADOPTION ON THE STEPPES AND IN CHINA

Now that the presence of foreign Brahmanas has been established, we must also ask ourselves how quickly could they be assimilated into societies of the Sinosphere. Unlike India where lineage was too heavily stressed, people in the East were more willing to adopt children for the continuation of their family line. Adoption of a son-in-law or even a son was fairly common in case a family was childless or the child could not continue the family business. Upon adoption, the adopted child or adult would usually give up his previous surname and take on the new family name. Adoption often happened across lines of race, class or status.

To give a few quick examples — the young Liu Yanshou was captured in a raid by Zhao Dejun. Liu Yanshou took on the surname Zhao from that day forward and fought alongside him in many battles. We also see that adoptive sons could outdo biological sons at times. The last emperor of the Later Tang, Li Congke was born to an unnamed father of the surname Wang but was adopted by the previous Emperor Li Siyuan who bestowed the Li surname upon him. Li Congke took the throne by overthrowing the Emperor’s biological son Li Conghou. Adoptions could also run across completely different cultures and still result in stark shifts of power. In 311, Shi Le, from the Jie barbarian tribe, captured an 11-year-old kid Ran Zhan whom he gave to his brother Shi Hu for adoption. Ran Zhan’s name was changed to Shi Zhan and he had a kid named Shi/Ran Min. Shi Hu was impressed by Ran Min and adopted him as a son as well. Shi Hu was an insecure ruler who dominated his state through terror; murdering his heir, the heir’s wife, and twenty-six of his biological children. Ran Min however continued to make his way up the ladder and in 349, when Shi Hu died — Ran Min seized control and carried out a huge massacre of all non-Han population in the capital region.

From medieval times, the tales of Chinggis Qa’an are very famous and don’t need to be told again. Chinggis’s mother Hoelun had adopted many orphans and treated them as her children as a part of the Khan’s integration policies. Two notable mentions here would be Shigi Qutuqu who served as one of the top officials in the Mongol Empire and the Shaman Kokochu Teb-Tengri, who eventually had to die because of his fallout with Chinggis’s brother Temuge.

If people in the Sinosphere were willing to adopt or intermarry, were Brahmanas willing to settle, despite their strict ritual observations which would not allow this? To answer this, we shall take a look at this tale from Mahabharata’s Shanti Parva:

Bhishma said, ‘I shall recite to thee an old story whose incidents > occurred in the country, O monarch, of the Mlecchas that lies to the > north. There was a certain Brahmana belonging to the middle country. > He was destitute of Vedic learning. One day, beholding a prosperous > village, the man entered it from desire of obtaining charity. In that > village lived a robber possessed of great wealth, conversant with the > distinctive features of all the orders of men, devoted to the > Brahmanas, firm in truth, and always engaged in making gifts. > Repairing to the abode of that robber, the Brahmana begged for alms. > Indeed, he solicited a house to live in and such necessaries of life > as would last for one year. Thus solicited by the Brahmana, the robber > gave him a piece of new cloth with its ends complete, widowed woman > possessed of youth. Obtaining all those things from the robber, the > Brahmana became filled with delight. Indeed, Gautama began to live > happily in that commodious house which the robber assigned to him. He > began to hold the relatives and kinsmen of the female slave he had got > from the robber chief. In this way he lived for many years in that > prosperous village of hunters. He began to practise with great > devotion the art of archery. Every day, like the other robbers > residing there, Gautama, O king, went into the woods and slaughtered > wild cranes in abundance. Always engaged in slaughtering living > creatures, he became well-skilled in that act and soon bade farewell > to compassion. In consequence of his intimacy with robbers he became > like one of them. As he lived happily in that robber village for many > months, large was the number of wild cranes that he slew.

The story ends with Brahmana Gautama eventually returning to his original ways after he came across a friend from his hometown. The Brahmana here had travelled to the country of the mlecchas up north, learnt archery and hunted cranes for meat. All of these are features of nomadic societies of the steppes. Perhaps this would also corroborate with evidence from the Book of Wei which speak of a Brahmanist Hu kingdom somewhere around Tajikistan. What is worth extracting from this episode is the fact that Brahmanas were willing to assimilate into steppe societies if required.+++(4)+++

It shouldn’t be too surprising as Brahmanas across India and South-East-Asia have regularly followed a pattern of marrying into the local priestly castes and subsuming it or marrying into nobility. The nastika monk Amoghavajra whom we discussed earlier too was born to a Sogdian mother in Samarkand to a Brahmana father.+++(4)+++ There is also the famous example of Kumarajiva who was born of a similar union himself and was later forcefully adopted as a son-in-law by Lu Guang.+++(4)+++

TRANSCRIPTION OF THE NAME

The final issue that is to be resolved is transcription. Chinese uses a logographic system of writing and lacks a phonetic system. It implies that there are fixed sounds associated with symbols that translate into words representing the meaning of the object concerned. Thus in many cases, the transcription may mask the true meaning entirely behind it. In other cases, the same sounds may be used to mean different things based on the radicals used in writing. Thus, firstly we ascertained the whole Rouran episode indeed uses the radicals 婆羅門 for transcription in all relevant volumes of the Book of Wei & Histories of the Northern Dynasties. Our friend @ShreshtVenkat also confirmed that there were no articles concerning incorrect transcription of 婆羅門 in Chinese academic circles.

Then upon receiving instructions from Professor Golden, we went through Pulleybank’s Lexicon of Reconstructed Pronunciation to get the reconstructed pronunciation of 婆羅門 in early middle Chinese. It turns out as follows:

婆 Po —> Ba [38:8]

羅 Luo —> La [122:14]

門 Men —>Men [69:0]

婆羅門 —> BaLaMen

The Ra ←→ La is rather common and understandable, which leaves us with BaRaMen which is a good approximation of Brahmana. This was again further confirmed by @ShreshtVenkat who went through the Korean and Japanese transcriptions, where the latter is popular in preserving Tang Era pronunciations.+++(5)+++ The Korean and Japanese transcripts were 바라문 [BaRaMun] and ばらもん [BaRaMon], again all good approximations of Brahmana.

Finally, we once again requested Professor Golden to give his word on the reconstructed pronunciations. He shares with us that the Rouran spoke the Mongol language as confirmed by the Brahmi Bugut inscription from the 580s. Professor Golden informs us that there are no Mongolic etymologies that come to mind regarding BaLaMen. This was a huge concern for us because our entire effort would be wasted if we ended up speculating in a place where there were already existing etymologies for the Khan’s name. With this information with us, we can now speculate on the roots of the much more apparent choice we have — Brāhmaṇa.

It should be noted that the authors of the Book of Wei and the Histories of the Northern Dynasties were well acquainted with the presence of Brahmanas. This is because there were enough records circulating which mentioned them alongside their own. We have also seen that Indians in general received special treatment as opposed to other foreigners. Let us assume for a moment that there existed some alternate etymology “X” in another barbarian language which roughly gives the approximation BaLaMen. Would the writers, who are very conscious of the fact that 婆羅門 refers to Brahmanas use the same radicals to denote a barbarian’s name? To answer this we further explored our records to find words which share a sound with BaLaMen:

䐗兒弟徽,字榮顯,小字苟兒。聰敏有氣幹,為任城王澄所知賞。景明中,起家奉朝請。延昌中,假員外散騎常侍,使於嚈噠,西域諸國莫不敬憚之,破洛侯、烏孫並因之以獻名馬。 >

Gao Hui [ 高 ] 徽 , who styles himself Rongxian 榮顯 …during the > Yanchang reign period [512-515], as Acting Supernumerary Cavalier > Attendant-in-ordinary, was sent to the state of Yedaon a diplomatic > mission. All the various states in the Western Regions respected and > feared him, and Poluohou 破洛侯 and Wusun 烏孫 presented famous horses > through him. He was appointed the Supervisor of the Entourage after he > had returned.

The PoLuoHou [破洛侯] above is the transcription of Bahanna, as accepted by all scholars, and that corresponds to modern-day Ferghana valley. It should be noted that although the sounds are matching in both Brahmana [婆羅門] and Bahanna [破洛侯], the same radicals could’ve been used in the transcription of both words but they weren’t chosen.+++(5)+++ This allows us to believe that the authors of these imperial histories did not want any undue confusion and likewise could’ve chosen different radicals for transcribing the possible alternate etymology “X” we discussed earlier. The authors here have very clearly made a conscious choice in their selection of radicals for the transcription. This choice could have been made because of only one possible implication — that the Khan in question is indeed a Brahmana.

Another doubt that comes to one’s mind is that a Brahmana being named Brahmana simply is quite odd. Well, it might be odd for us here but we know of the same nomenclature being employed for another Brahmana in the Northern Wei Era, the same period as our YuJiuLu PoLuoMen. The Old Book of Tang, Volume 32 tells us the following:

後魏有曹婆羅門,受龜茲琵琶于商人,世傳其業. >

In the later [Northern] Wei Dynasty, there was Cao Brahmin [曹 > 婆羅門**]**, who received the Guizi lute from a merchant and passed > on his profession to the next generation.

We hear of a Cao Brahman from the Northern Wei who used to play the Kuchean Lute he received from a merchant and passed the profession to his children. The Cao [曹] radical appears before the Brahmana one, suggesting it is a surname. In light of this, a name like YuJiuLu Brāhmaṇa [郁久閭 婆羅門] wouldn’t strike us as necessarily odd.

Finally, one may also ask why mustn’t the name simply imply conversion to Hinduism. It can, however, we are aware of plenty of steppe people who converted to other religions, Hinduism included, but didn’t take on an ethnonym. Typically they were named after gods or took regular Sanskrit names.

The Turfan Documents and Conclusion

Now that established the prerequisites to such an arrangement, we should discuss more immediate and probable causes behind why a Brahmana might have been adopted by the YuJiuLu clan. This is not a necessary activity since their presence in Northern Wei is well-established. So, it would be natural that they are also present in the Rouran, who served the Northern Wei often and were neighbours to the many Indianized kingdoms of Central Asia. However, we believe that figuring out the immediate probable cause behind such adoption will give more weight to our theory here.

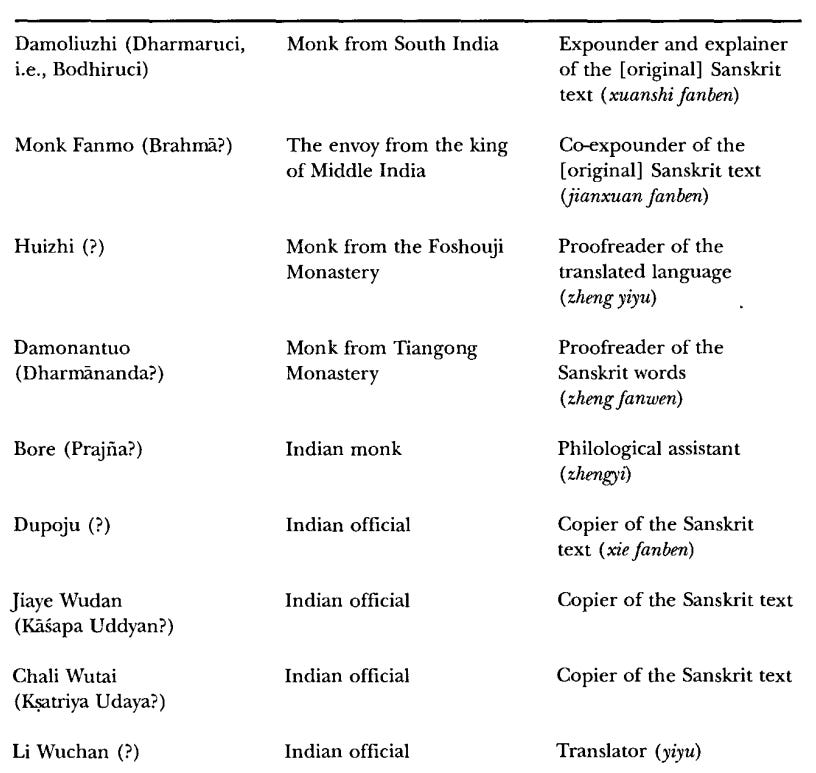

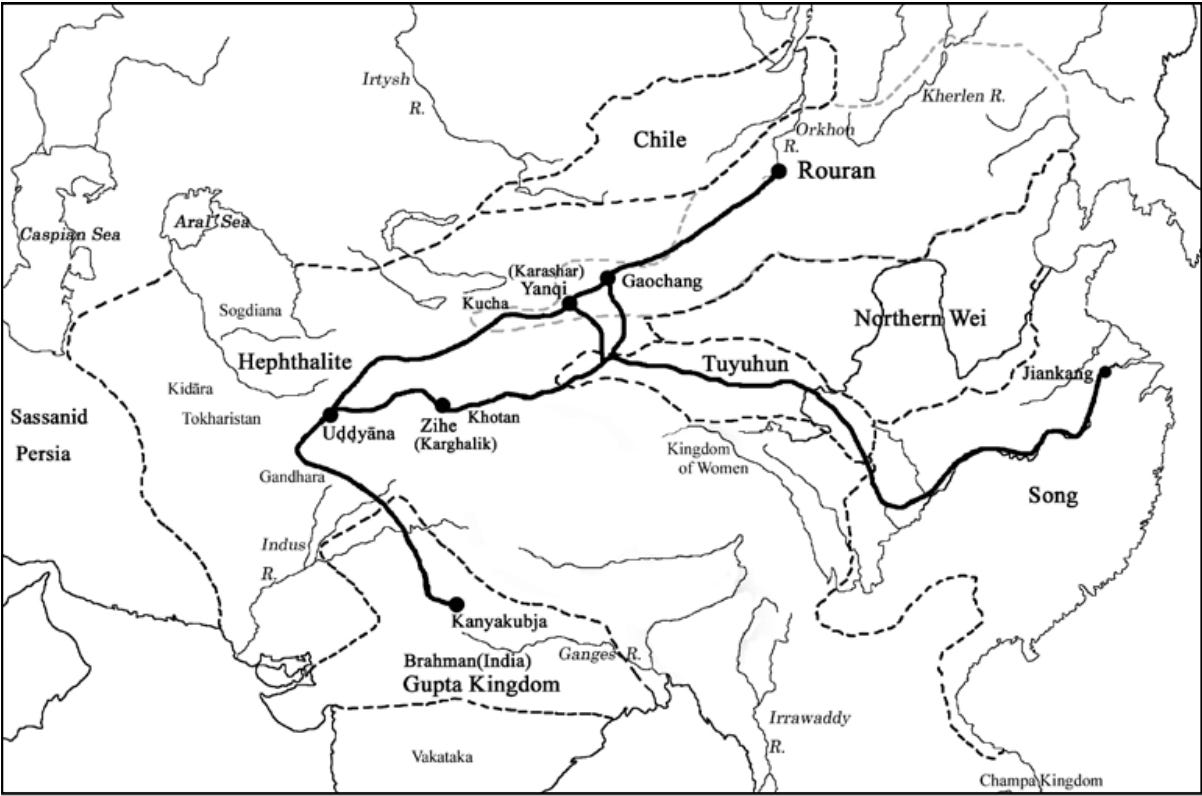

World Map in 475 AD (Wikipedia)

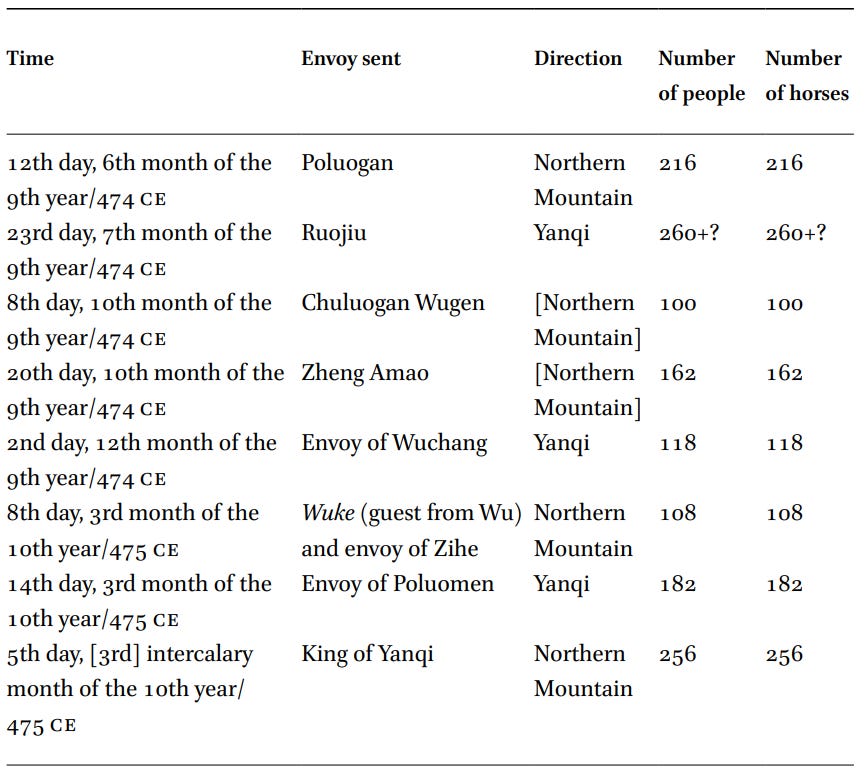

In the latter half of the fifth century, the Rouran Khaganate marched westwards towards Khotan having brought Gaochang into submission. Their westward march had forced Hepthalite Hunas, who were vassals of the Rourans to push west and pour into the Sassanid and Gupta Empires, eventually dominating most of central Asia. In this time of chaos, minor kingdoms reached out to the Rouran Khaganate and the Northern Wei dynasty hoping for help. Many of these were recorded in the Book of Wei and some more records were found in the Turfan documents which were excavated in 1997. Useful information from it is:

十年三月十四日,送婆羅門使向鄢耆,高寧八十四人、橫截卌六人、白艻卅六人、田地十六人,合百八十二人;[每人出馬]一 > 疋。 >

On the 14th day, 3rd month of the 10th year, to escort envoys of > Poluomen [India], 84 people from Gaoning, 46 people from Hengjie, 36 > people from Baiji, 16 people from Tiandi, in total 182 people; each > person sent one horse.

The list of envoys to the Rouran mentioned in the Turfan Documents

The envoy from the Kingdom of Poluomen undoubtedly refers to envoys from India, which was described as Brāhmaṇadeśa.+++(5)+++ As the famous Nastika traveller Xuanzang describes in his travelogue:

On examination, we find that the names of Tianzhu 天竺 [India] are > various and perplexing as to their authority. It was anciently called > Yuandu 身毒, also Xiandou 賢豆; but now, according to the right > pronunciation, it is called Yindu 印度….

The families of India are > divided into castes; the Brāhmans [Poluomen: 婆羅門], particularly > [are noted] on account of their purity and nobility. Tradition has > so hallowed the name of this tribe that there is no question as to > difference of place, but the people generally speak of India as the > country of the Brāhmans.

The document speaks of two different Indian envoys. One from Wuchang, which is Uddayana and the other from the Kingdom of Poloumen, a more southern region which most scholars identified with the Gupta Empire. The Poluomen envoys who set out for the Rouran in 475 and were returning must have visited them to establish connections to fight the growing Hepthalite power. We are also aware of an embassy to the Northern Wei in 477 and five more embassies from kingdoms of south India between 502 to 514.

An envoyship from one of the biggest kingdoms in the world would’ve surely been treated well within the Rouran. Furthermore, as we already saw, around this time Brahmanas held much fame and were sought for their expertise in medicine, mathematics, astronomy and esoterica. Steppe people have always been fascinated by non-Han intellectuals in particular. It would not be impossible for a young Brahmana to be adopted by the ruling YuJiuLu family who would be interested in these things. Such adoption would also signal more permanent friendly ties with the Gupta Empire, which would be beneficial as it was one of the only powers that could possibly keep a check on the Hepthalites in their West. Thus, the adopted Brahmana is raised as a cousin to Anagui, as was common in the steppes and is known as such to the Northern Wei authors. As far as why we are uninformed of this — it is because of the lack of information in the Chinese sources because of the little attention that is paid to YuJiuLu PoLuoMen. Even his father isn’t named but he is just called Anagui’s cousin after all. If perhaps he was as significant as his cousin Anagui or raised in China then more could’ve been known about him.

So to put things together — under the threat of the Hunnic invaders who had settled in Gandhara by 460 and captured Sindh by 480, Emperor Kumaragupta II sent an embassy of more than 182 men, all the way out to the Rouran Khaganate. The Hunas were the vassals of the Rouran and remained so until the 520s but their growing power was always a cause of distress for both the Gupta and the Rouran who could benefit from a relationship. This embassy reaches Ting, the Rouran capital lying somewhere in modern Mongolia, northwest of Gansu, in 475. During this frame, either by marriage or adoption, a Brahmana is assimilated into the Mongolic people. This could’ve happened for a variety of probable reasons as discussed, out of curiosity to learn Brahmana alchemy, magic, medicine, mathematics or script. Alternatively, it would be useful to station a permanent ambassador in the Rouran to the Gupta as well whose son could’ve been assimilated later.

Either way, our guy grows up with the Rouran and has the surname of the ruling clan bestowed upon him, which was not particularly unusual again and enjoys privileges as nobility. Sometime in 520 after the death of Chounu Khan, the Brahmana’s now-cousin Anagui takes the reigns but soon after he’s met with a rebellion by one Qilifa Shefa who kills Anagui’s mother and younger brother, forcing him to flee to the court of the Northern Wei Emperor Xiaoming. It was during this chaotic period that our Brahmana seizes power and declares himself the Khagan. He is titled Mioukesheju Khan, which was the Wei word for peaceful and quiet. Anagui meanwhile becomes restless at his loss and requests troops from the Northern Wei Emperor to recover his domains. However, his courtiers reject the idea given how the unpredictability of the situation. Going lightly and without planning would only damage the Emperor’s prestige. In February of 521, the Emperor sent one envoy Gouren to the Brahmana, ordering him to retake Anagui. However, Gouren didn’t treat the Brahmana with the respect a sovereign deserves, which made the arrogant Brahmana decline the offer.

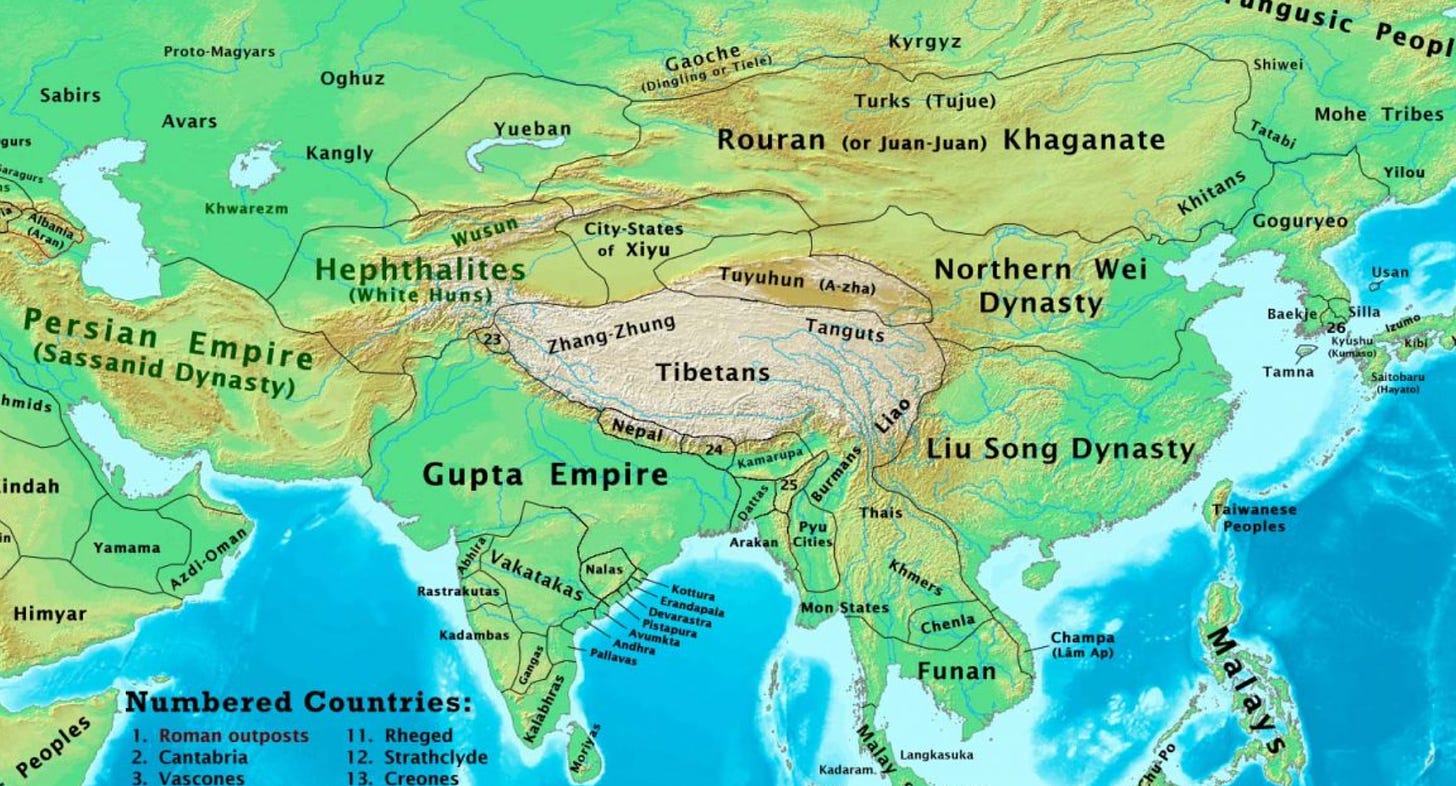

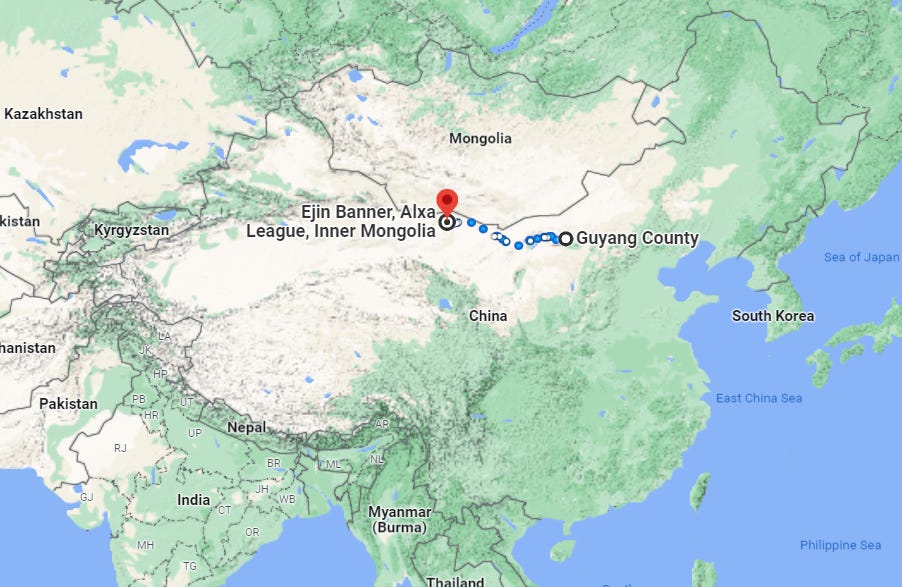

Locations of modern Huaishou (Guyang in Inner Mongolia) from where Anagui ruled and Xihai (Ejin in Inner Mongolia) where Brahmana ruled.

Soon after, another chaotic uprising began, as was expected. Qilifa Shefa and the Gaoche Turks attacked the Brahmana and minor nobles all across the Khaganate rose in revolt against him and one another as well. Having lost power, the Brahmana had to accept a compromise with the Northern Wei Emperor who partitioned the Khaganate in two halves. Anagui would rule from Huaishuo in the East, and the Brahmana would rule from Xihai in the West. His rule wasn’t successful and we learn that sometime between he raided the bordering towns of Liangzhou in search of food since his men were dying of hunger. The Brahmana later decided to flee to the Hepthalites, to his brother-in-law Yeda. However, he is soon brought back to the Northern Wei court and put under arrest, where he eventually died in 525. We don’t learn anything about his descendants just like we learnt nothing about his ancestors. He doesn’t seem to be survived by anyone significant.

On a final note — we’ve followed only strictly accepted facts all > along the post, however, our conclusion and weaving might sound a bit > odd to some readers. Unfortunately, we couldn’t come across any > academics who took note of this matter — not a single paper even > attempted to conjure an etymology for PoLuoMen. On the Chinese side, > we do come across one article here: > https://www.toutiao.com/article/6742465628998730247/?wid=1680211525218

It doesn’t answer the question at all however, it hastily says that > Brahmanism was popular in those times thus the Rouran Khan took that > name under its influence. As we have recited previously in our essay > here, there are plenty of records of Steppe people converting to > Hinduism but not a single one where they took the name Brahmana. > Usually, they followed typical Sanskrit names or those of gods. There > is the possibility that he named himself Brahmā but he was called > “Fan” and nothing close to PoLuoMen or BaLaMen. For what it is worth, > Dr Ulrich Theobald writing for the China Knowledge, translated YuJiuLu > PoLuoMen as YuJiuLu Brahman here: > http://www.chinaknowledge.de/About/about.html > Furthermore, we had shared our theory with the doyen of Turkish > studies Professor Golden, who found it very intersting and encouraged > us to pursure it. Without his approval — we would have surely binned > this idea. > To put things simply — while there indeed exists no confirmatory > evidence for our theory being true or of it being false either — we’ve > established fairly reasonable grounds for acceptance (px>0.8) in this > exercise. Thanks a lot for reading, we hope you enjoyed and learned > new things regardless.