Source: here.

Getting a sense of the Russian soul

Share this post

Getting a sense of the Russian soul

razib.substack.com

Copy link

Getting a sense of the Russian soul

Looking into Russian genetics and history (not through Putin’s eyes)

[TABLE]

Subscribe

For many of us actual Cold War kids, the Soviet Union, the Eastern Bloc and the battle between capitalism and global communism were just background conditions of our youth. But at least in the United States, what we really talked about wasn’t the Soviets or the communists so much as the “Russians,” conflating the dominant Soviet ethnicity with the whole nation. Though Russians were only 50% of the population of the Soviet Union, Russian language and culture dominated the USSR. Despite being the bulwark of international communism, by the time Josef Stalin led it in the 1930’s, the Soviet Union was for all practical purposes the heir of the Russian Empire. This is how a prominent Stalin expert could refer to his subject as the “Red Tsar.”

The abstract rivalry between global alliances and ideologies, between First World capitalism, and Second World communism, was the concrete battle between Americans and Russians. In 1985’s Rocky IV, Dolph Lundgren’s Captain Ivan Drago is a towering figure of Russian muscle, the perfect villain for Sylvester Stallone’s plucky American underdog, Rocky Balboa to defeat. And a national rivalry was seen as such an eternal background condition of existence that the original Star Trek, set centuries in the future, had to have a Russian character, Pavel Chekov, to indicate a rapprochement between the two great powers.

As a child of the 80’s, I can attest to the fact that while the Cold War may have had its ups and downs, at the time most of us saw the American-Russian rivalry as a perpetual fact of the geopolitical landscape. Despite Ronald Reagan’s optimistic rhetoric about defeating the “Evil Empire,” the rapidity of communism’s collapse and the dissolution of the Soviet Union came as a shock. Almost overnight, “Russia,” what was the Soviet Union, was no longer a vast nation-state that stretched from Europe to the Pacific, enfolding within its frontiers everything from chunks of Eastern Europe to Afghanistan, but a more modest, albeit still massive, country, the Russian Federation. “Russia” was finally just Russia. That it was now officially called the Russian Federation was just a footnote.

In the 1990’s, Russia faded from the American consciousness, with occasional newsworthy exceptions like the internecine violence during 1993’s constitutional crisis or the worldwide panic its 1998 financial collapse triggered (don’t ask me if anything specifically good happened in Russia in this period. I couldn’t tell you, because the American media didn’t run those stories). On the geopolitical front, it was all quiet on the Russian front until 1999’s NATO intervention in Kosovo, when President Boris Yeltsin objected to the West’s move against Serbia, a Russian ally historically. But change was in the air. On December 31st, 1999, Yeltsin resigned, and a then-obscure Vladimir Putin became President of Russia. Yeltsin had been a reformer during Mikhael Gorbachev’s time, but as the leader of the Russian Federation in the 1990’s he oversaw the rise of oligarchs who came to dominate a society riddled with corruption, while the state became a cat’s-paw for Western social engineers experimenting with neoliberal economics. Yeltsin’s descent into alcoholism and personal chaos paralleled the hedonistic anarchy of 1990’s Russia.

This is the ship of state and society that Putin righted. His suppression of a violent Islamist rebellion in Chechnya, persecution of the oligarchs, and an ideology of a strong and muscular state, were viewed as evidence of a sinister turn in the West, an end to our dream of a liberal democratic Russia. But as is usually the case, it wasn’t that simple. Suppression of the Chechen revolt saw massive human rights violations, but many Westerners ignored the real casus belli: Islamists based in a de facto independent Chechnya violently attacking neighboring regions, spreading terror as far afield as Moscow.

In the West, oligarchs like the late Boris Berezovsky were seen as bulwarks of liberalism and free speech, but Russians widely viewed them as corrupt gangsters plundering public resources with impunity and living above the law (Berezovsky was an alleged rapist with a taste for young teens). Finally, the reemergence of a strong central state was a shift back to the traditional pattern Russians had known, not a new authoritarian innovation suddenly imposed upon a populace that cherished the Rights of Englishmen. Putin waxed in popularity across the aughts in Russia because he brought order and ended chaos for the common people. If he rules until 2030, his tenure will have matched Stalin’s, and he may actually appreciate the parallel.

Even Americans now acknowledge that in the decade after the Soviet Union’s collapse when Russia fell off most American radars, it did not achieve an idyllic end of history. We heard tales of an American-style liberal democracy rising from communism’s ashes, not the dispiriting mobster rule that Russian citizens were enduring. There were always signs that the narrative the American public was fed was missing something. I remember in high school wondering how freedom-loving, liberal-democratic Russia could have a life expectancy of 65 in 1994, already four years shorter than in the final years of communism. If they were so much better off under democracy and capitalism, why were they dying in such numbers? We now know that crash was largely driven by massive increases in alcoholism among men.

In 2022, Russia’s self-conception is again a matter of importance, and Putin has reclaimed for his nation the geopolitical center stage. He has become a truly reviled figure in the West, the personification of the evil dictator archetype. But in Russia, he has long had a broad base of support. Even Gorbachev, who ended the communist order, went on to endorse Putin in 2007.

In the 20th century, we tried to understand Russians, from their history to their culture, because of the Soviet Union’s global importance. The study of Russian history and culture was not simply academic; it had essential applied relevance during the Cold War. Then, for most of the decades after the fall of communism, Russia was not of deep interest, the academic field atrophied and public attention slackened (Russianist Condoleeza Rice, for example, had to transfer her skills and expertise to grappling with Middle Eastern geopolitics). In 2012, Barack Obama famously dismissed Mitt Romney’s assertion about the importance of Russia and its threat to American interests. Despite Russia’s reality as a petrostate, for most 21st-century Americans, it is simply the land of vodka, models and oligarchs.

But Russia has made itself matter again. Since before the 2016 US election, Russian propaganda operations have become incredibly entangled in American politics, and broad swaths of the US citizenry view Putin and the state he heads with deep hatred. The invasion of Ukraine in 2022 unleashed a far more fearsome wave of anti-Russian sentiment.

But performative public responses like adding the colors of the Ukrainian flag to corporate logos, banning Russian cats from shows and removing Russian films from festivals don’t get us any closer to understanding the crisis in Ukraine. Clearly, we need to update our understanding of Russia and Russians. Who are they really? What do their roots tell us about their past and their expectations of the future? And fundamentally, how do they see themselves? The key to Russian self-conception obviously is not to be found in 1991, with the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Nor will the 1917 October Revolution that ushered in the communist era shed much light. Russia’s origins as a nation go back to the arrival of the Swedish Viking Rurik in the city of Novgorod nearly 1,200 years ago, and the subsequent conquest of Kiev by his sons. Russian identity is deeply rooted in the conversion of his great-grandson, Vladimir, prince of Kiev, to Greek Christianity in 988 AD. The Russian soul retains trauma from the arrival of the Mongol hordes in the 1250’s, two centuries that they refer to as the “Tatar Yoke.” Likewise, Russians continue to feel widespread pride at the expansion of the vast Russian Empire, which spanned the continent from Poland to Manchuria by the 1600’s.

Putin’s behavior is obviously beyond the pale, but what do you do from this vantage? Some lose themselves in the catastrophe porn pouring out of the besieged country in recent weeks. Others suddenly develop a deep interest in transliterations from the Cyrillic and take up policing those who find it immaterial whether you spell it Kiev or Kyiv. Either way, neither the one nor the other took any interest in the beleaguered capital before last month. Hard to believe our transliteration choices on Instagram and Twitter will impact the morale of the refugees streaming west. But it’s a free country.

In the end, perhaps you can argue that one costless gesture is as good as any other. Maybe so. You get to feel slightly less passive while alas changing little or nothing for the good people of Ukraine. My personal tastes don’t really run to these symbolic gestures, but I share a need to do something germane, even knowing it won’t make any immediate difference. First up, books, of course. Here is a reading list as many have requested, to go deeper on the history of the region. And second, what follows is my attempt to actually contribute new analysis to the conversation about Russia and the former Soviet republics stuck in its orbit: a closer look at what 21st-century genomics can add to our understanding of the last millennium or so of human history across Russia, Ukraine and their neighbors.

The genetic goulash that is Russia

To understand the position of Russians in the context of Eastern Europe and Asia, as well the demographic forces that shaped them and their neighbors, I wanted to explore patterns of genetic relatedness across various populations. I began with 478 Russians, and compared them to 419 Poles and 142 Ukrainians (the next two most populous northern Slavic groups). I also wanted to explore the relationship of Eastern Europeans to nations to their west, so I added 91 English, 99 Finns and 13 Germans to represent Northern Europeans, plus 20 Greeks and 28 Sardinians to represent Southern Europeans. The 19 Serbians are a South Slav group, and offer a check on whether there is anything distinct about Slavic ancestry. The 15 Karelians are a Finnic group on the Russian side of today’s border with Finland, while the 15 Mari represent a Finnic group located on the western slopes of the Ural mountains. I added these far northern ethnicities to see if there is a Uralic cluster analogous to a Slavic one, and also to test possible contributions of this element to Russian ancestry. Finally, I included 30 Georgians, 23 Tatars, 12 Mongols and 28 Yakuts in order to detect possible non-European ancestry in the Europeans.

Before we proceed, I want to note I removed all Ashkenazim from the dataset (a large number of people who report four grandparents having origins in Poland, Ukraine and Russia in the solid American data sets from which I culled these self-identified samples are of Jewish background), as their history in Northeast Europe dates to after 1000 AD and is very distinct and separate from neighboring populations since they maintained their endogamy for most of the last millennium.

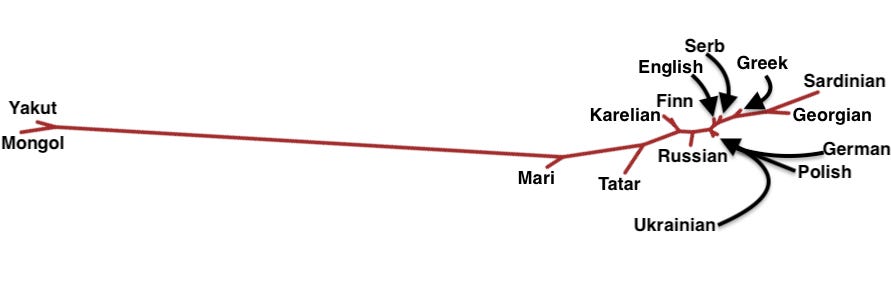

First, I computed pairwise genetic distances between all the populations. The genetic distances represent the variation across 200,000 meaningful genetic markers, or SNPs, and are distinct between the two populations. I mapped the 105 unique pairwise comparisons between the populations onto the tree above. Populations with a very small genetic distance bunch together on the tree, while those with a large distance appear far apart.

The Poles, Germans and Ukrainians are so close on this plot the differentiation is barely visible (to give a sense: the value for German to Mongol is 0.087, German to Sardinian 0.013 and German to Pole a mere 0.0005). The Karelians and Finns are similar, as you would expect. The English and Serbs are shifted toward the Southern Europeans, while far to the left, you see the two Asian groups, Mongols and Yakuts, the latter of whom (as you might remember from the game Risk) are a Central Siberian population, and the northernmost Turkic speakers in the world. The Tatars, Turkic-speaking Muslims who traditionally lived to the west of the Volga river, are shifted toward Asians but cluster near the European populations. The Mari, whose main claim to fame is that they are the only European ethnic group who were never fully Christianized, drift considerably more towards the Asian node than their western Finnic cousins, but that is not surprising considering they are literally on the easternmost edge of geographic Europe.

This brings us to the Russians. Unlike the Poles and Ukrainians, they do not cluster with the Germans. Rather, they are positioned more toward the eastern populations. This is in keeping with the fact that Russians did spread eastward (and north) from their East Slavic neighbors. They are shifted toward Tatars but are clearly distinct, contra 19th-century Western European Russophobic assertions that if you “scratch a Russian you will find a Tatar.” But this is a population-wide summary that masks and hides variation within populations. Let’s next look at the individuals using principal component analysis (PCA), where genetic variation is plotted on two dimensions:

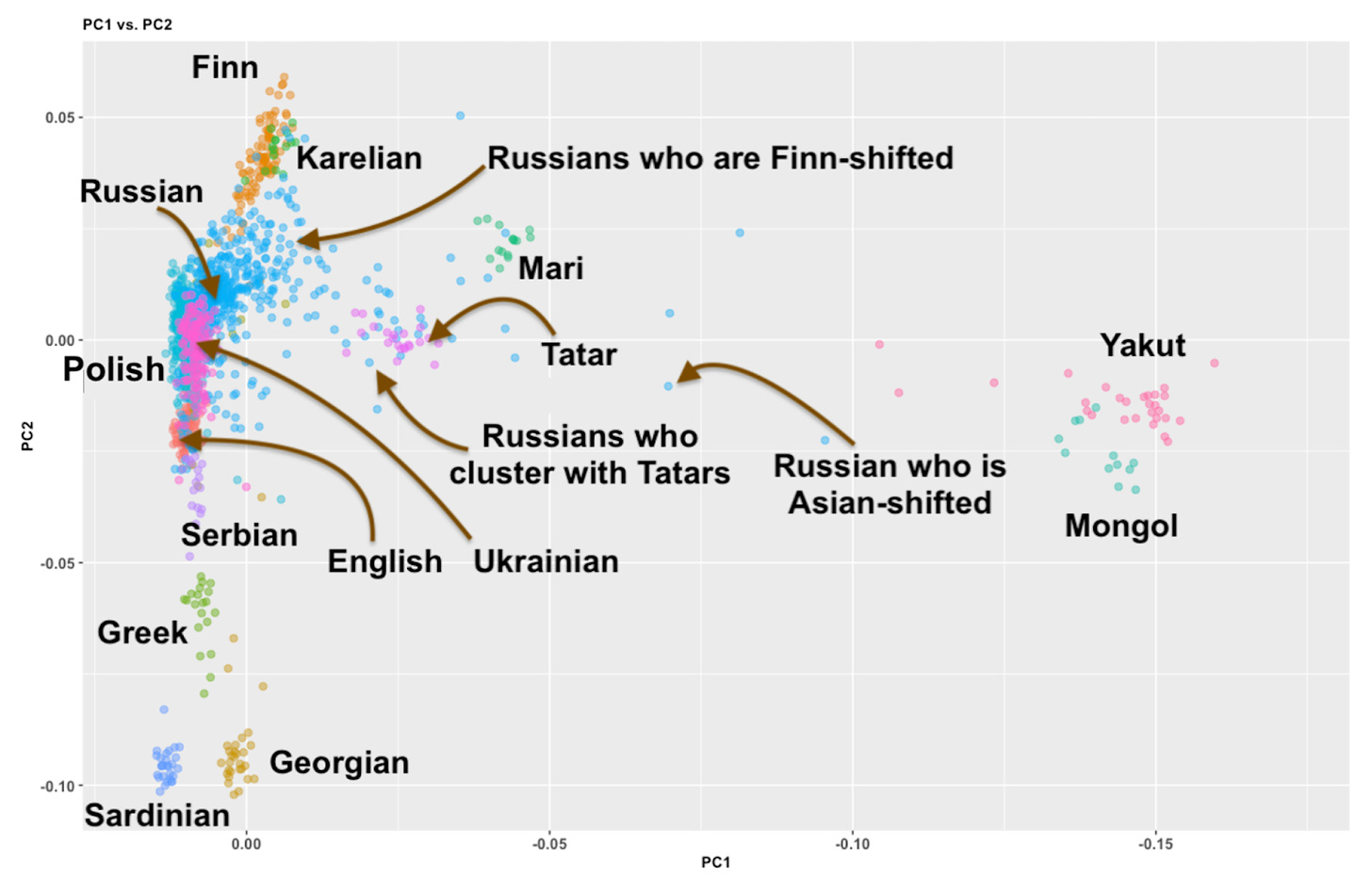

This plot is more informative than the tree. Each individual is positioned on the chart based on genetic relatedness, with genetic similarity from person to person represented and color-coded by population cluster. The x-axis is a west-to-east plane geographically (European to East-Asian, running left to right), while the y-axis is a north-south axis, within both Europe and Asia. You can see that some of the populations appear cleanly as discrete clusters. This is the case with Georgians and Sardinians, whereas Greeks and Serbians both show a stretched-out range with variable levels of affinity to Northern Europeans. This reflects early medieval Slavic admixture that resulted in Serbians emerging as a Slavic-speaking Balkan population, a fusion of natives and migrants, while many northern Greeks from Thessaly have clear Slavic ancestry despite their fully Hellenic culture.

The Finns also exhibit a range of affinity to other European groups, but they are still quite distinct, due to their genetic isolation and history of bottlenecks. The Finns’ Karelian neighbors are quite close to them as individuals on this plot. Also expected due to geographic and ethnic affinity. The Tatars and Mari are both shifted to East Asians as a whole as you’d expect, though still closer to Europeans overall on the PCA as well. Notice that the Tatars are south of the Mari on the y-axis. This reflects the reality that the Turkic ancestry within the Tatars tends to be from the southern region of Siberia, with some of it having mixed with Central Asian populations. In contrast, the Mari, as a Finnic people, have Siberian ancestry from more northerly tribes, as ancient foragers traversed the territory on the very edge of the tundra.

Finally, the three populous Slavic groups, Russians, Poles and Ukrainians, dominate the left edge of the plot, along with the English and the Germans (who are shifted towards Southern Europeans in a relative sense). Unlike the Russians, on an individual level the Ukrainians exhibit very little variation in distance from Asians, and are quite similar to the Poles, as the earlier genetic distance plot also showed. The lack of Ukrainian genetic diversity is no surprise. As Ed West observed, in the 19th century, Ukraine’s was a wholly peasant culture, meaning that after centuries of foreign rule there were actually no true ethnic-Ukrainian cultural, political and economic elites. Poland and Lithuania’s elites had traditionally governed Ukraine, while the region’s conquest by Imperial Russia in the 17th and 18th centuries meant a new era of rule by outsiders (Catherine the Great, the most famous ruler of the Russian Empire in the 18th century, for one, was German). At the dawn of articulation of 19th-century nationalism, an ethos predicated on linguistic affinity and an elite stratum propagating a common literary culture and history, was hampered in Ukraine due to its leadership class being entirely ethnically alien (Lithuanians, Latvians and Finns faced the same problem).

Meanwhile, despite being from the same original stock as their southern and western neighbors, the Ukrainians and Poles, Russians have long been diverse in their origins. In the 16th century, Ivan the Terrible quipped that he himself was not even Russian, as his paternal grandmother was Greek, while his mother came from a powerful noble house with Hungarian and Mongol ancestry. The group of ethnic Russians with strong affinities to Tatars apparent in this data is not surprising because there are many historically attested cases where opportunistic steppe-land arrivistes converted to Orthodox Christianity and assimilated into the elite of Muscovy. The first non-Rurikid Tsar, Boris Godunov, was from a noble house with Tatar origins, as was Peter the Great’s mother.

But a quick look back at the PCA plot shows that even more numerous than the Russians with clear Tatar affinities are those shifted toward Finnic populations. The addition of this component to Russian ancestry probably owed to the migration of Slavic peasants and fur traders northward, into the cold taiga forests then occupied by indigenous Finnic tribes. While the relationship between Tatars and Russians has often been violent, the Finnic tribes of the sub-Arctic lands interacted with southerners mostly through trade. In the medieval period, the forested north supplied much of the world’s furs. It was the depletion of this natural resource that spurred the Russian conquest of Siberia and eventual expansion into Alaska. The Russians absorbed and integrated local Finnic populations gradually, out of the limelight of history and through the daily contact of “truck, barter and exchange.”

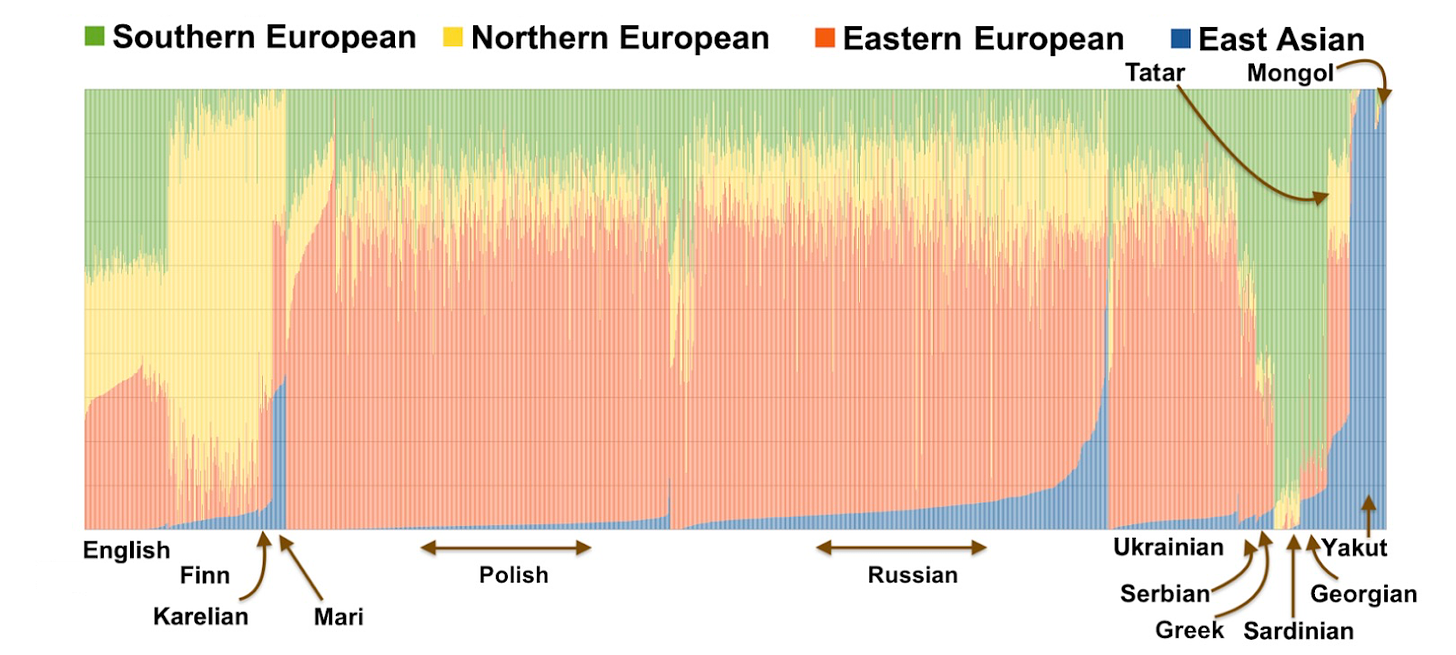

To further illustrate Russian genetic variation, I created an admixture plot to model all the individuals’ mixes of ancestry. The modeling software requires a presupposition about a number of ancestral populations, which I set to “at most four.” The algorithm simply looks at the whole population’s genetic variation, breaks it into however many clusters you decree, and then assigns individual proportions to each cluster based on the sample’s genes. For the purposes of this graphic I selected four clusters, trusting this would break out the Asian ancestry, as well as various directionalities in European ancestry (Southern, Northern and Eastern).

I’ve given tentative labels to the four broader clusters based on which populations they appear most commonly in. Remember, these are abstractions that the algorithm generated, but the relative cluster membership patterns are useful in exploring comparative differences in ancestry composition.

Just as on the PCA and genetic-distance tree, Ukrainians and Poles are very similar. Most of the Russians are just like the Ukrainians and Poles, but many individuals resemble Finns strongly, while others have more “East Asian” ancestry.

This general picture of Russian cosmopolitanism compared to Ukrainians and Poles is also evident in the paternal lineages, passed from father to son. Looking at a much broader dataset than just my 500 Russians, nearly 25% of the Y chromosomes from the Russian Federation are haplogroup N. This haplogroup is associated with Finnic people (80% frequency in Finnish men, for comparison), while only 5% of men in Poland and Ukraine carry this lineage. This indicates that whole forager communities culturally assimilated, including their elites. It was not simply a matter of southern Slavic men finding wives from collapsing local communities.

From Rus to Russia

If there is any Tsar Westerners know by name, it is usually the westward-focused Peter the Great, famous for dragging Russia into the community of European nations. Before Peter, the Russian Empire looked (and expanded) eastward, rather than west. But this had not always been the case with the East Slavic world, as the rulers of 11th-century Kievan Rus cultivated marital alliances with Western European powers (a Russian princess became the mother of 11th-century French kings).

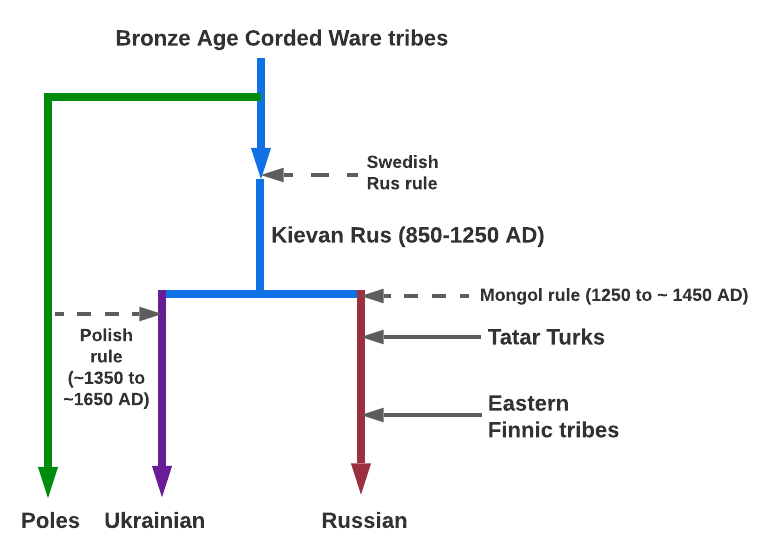

What changed Russia, and severed the world of Kievan Rus from the west was the Mongol conquest of the 1250’s and the subsequent Tatar Yoke under the Golden Horde. Bloomberg columnist Noah Smith has referred to the Russian Empire that emerged in the 16th century as a successor state of the Mongol Empire, and this is not an unreasonable assertion. It was the Mongol conquest that brought to prominence the little-known Rurikid princes of Moscow, then a minor town in the northeast, elevating the Danielovich line that would give rise to the Tsars. The rulers of Moscow retained their ancestral language and religion, but their participation in the political games of the steppe (including intermarriage with Genghis Khan’s Golden Family) transformed them in ways that likely gave Russian despotism a unique flavor.

Meanwhile, the southwestern portion of Kievan Rus, the old heartland, was put on a different path. The Mongols conquered Kiev in 1240 AD, but lost it in 1362 to the Lithuanians at the Battle of Blue Waters. In 1385 the Grand Duke Jogaila, the ruler of Lithuania, converted to Western Latin Christianity as he unified his Duchy with the Kingdom of Poland. This established a firm divide between the territories held by Poland-Lithuania and those dominated by the Orthodox rulers of Muscovy. While Kiev remained under Poland-Lithuania until 1667, the nascent Russian Empire focused on swallowing up the Golden Horde’s successor states, thrusting eastward into Siberia on a scale to make America’s 19th-century phase of Manifest Destiny seem quaint. In 1689, the Treaty of Nerchinsk established the border between the Chinese Empire of the Qing and the Russians in the Amur valley region. The drive to the east only came to an end when the Russians ran out of land at the Pacific.

As is clear from genetics, history and geography, unlike Ukraine or Poland, Russia is a vast and diverse land that transcends ecologies and continents. Though its core ethnicity are East Slavs, drawing from the same roots as the Belorussians and the Ukrainians, the Russians became a Eurasian-inflected ethnicity who were assimilative, absorptive and expansive. They were ruling a cosmopolitan empire-state, as attested by the 1915 construction of a Tibetan Buddhist temple in St. Petersburg.

Russia and Ukraine have many similarities, both superficially and substantively, but politically comparing them is a category error. At the United Nations, they are both present as nation-states, but the Russian Federation is a multiethnic and multireligious empire that is clearly heir to the Russia of the Tsars. Putin’s long-time girlfriend is a woman of Tatar Muslim background who converted to Russian Orthodoxy in 2003, a classic case in a long history of mixing between Russians and Turkic steppe people. Russia inherits a tumultuous history with disparate threads that stretch back more than 1,000 years. Ukraine, in contrast, is a self-made nation, new to the world in this form. It is a 21st-century heir to 19th-century European linguistic nationalism, its elites’ sensibilities being forged in this century through existential conflict with Russia and alliance with the West, as they consciously abandon the Russian language they were taught in schools in favor of Ukrainian.

The Empire Strikes Back

In the lead-up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Putin reiterated his position that Ukraine was simply part of historic Russia, with shared roots going back to Kievan Rus and no history of independent political existence. It is true that Ukraine is a new nation-state, analogous to modern Finland or Lithuania, both of which had been ruled by ethnically exogenous elites for centuries (Swedes and Poles, accordingly). But Putin conveniently ignores that modern Ukrainians share one thing with many of their western neighbors that Russians do not: they are not an imperial people. After the chaos of World War I, numerous small-to-medium-sized ethnostates were carved out of the interstices between the former Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires, and Ukraine resembles these more than it does the hulking Russian Federation to its north and east. An entity being new in the world does not mean it is any less real. Putin may be wishfully conflating antiquity with authenticity.

The Russians grew out of the cultural and historical ashes of Kievan Rus. While their Ukrainian cousins to the west suffered under the rule of Polish and Lithuanian landed elites, the Rurikid princes of the northeast received tutelage from the Golden Horde’s khans. Though the term tsar derives from caesar, the capricious behavior of rulers like Ivan the Terrible, who beat his own adult son to death in a fit of rage, reflects a despotism distinct from that of the earlier Rurikids of Kiev. Glib assertions that under the skin Russians are Tatars are false, but it is clearly true from both the genetics and history that Tatar elites did fuse themselves enduringly into the Imperial ruling class. This likely also had an effect culturally. Additionally, while Ukrainians and Central Europeans to the west descend almost entirely from peasants, a substantial proportion of Russians bear the stamp of descent from foraging Finnic tribes that ranged across the circumpolar lands for thousands of years, a cultural history totally alien to mainland Europeans.

It turns out that Putin’s often quixotic espousal of a Eurasian geopolitical and cultural vision faithfully reflects a stubborn historical strand that has marked the modern Russian soul. Ukraine, despite its strong ethnic, linguistic and religious commonalities with Russia, faces west and its national identity has never stood athwart two continents. Perhaps it is not surprising in hindsight that 20th-century global communism, with its multiethnic, imperial aspirations, was headquartered in Soviet Russia. Despite the prediction of orthodox Marxism that it should naturally emerge in the capitalist West, the 20th-century’s most imperial ideology gained purchase in the domains of the Russian Empire. Though at their root, Russians may be both genetically and culturally European, history has forged Russia into a civilization-state with a constitutive imperial ambition that will always clash with the more modest, cooperative aspirations of other peoples and nations. It may not have quite been inevitable, but where we are today should not surprise us. History may not be clockwork, but we can count on the past to echo long into the future. Whether we choose to listen or not is up to us.

Subscribe

| | | |———————————————————————————|—————————–| | 21 | Share |